TL;DR

Gippsland’s stunning landscapes, from Tarra-Bulga’s rainforests to Port Albert’s coast, sit atop a story over 100 million years old. In the Early Cretaceous, this region was part of Gondwana near the South Pole, home to polar dinosaurs, ancient forests, and swamps that later formed the oil fields beneath Bass Strait. This article explores how fire, ice, and deep time shaped the land long before people arrived.

How Gippsland Was Forged Beneath Ancient Ice and Fire

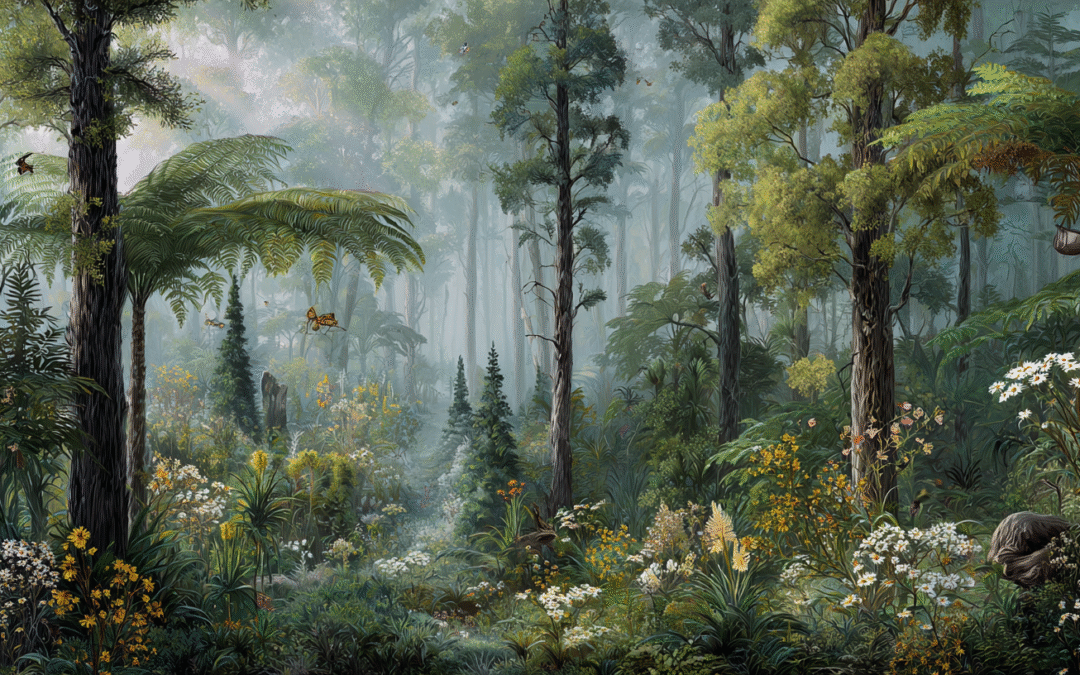

In the hushed canopy of Tarra-Bulga National Park, a fine mist drapes the myrtle beeches and towering mountain ash. It’s a world that feels ancient, and it is. But even this lush temperate rainforest is young compared to the forces that shaped Gippsland. To truly understand this landscape, one must step not centuries, but hundreds of millions of years into the past, to an age when Gippsland was not only far south of its current position, it was joined at the hip with Antarctica.

In the hushed canopy of Tarra-Bulga National Park, a fine mist drapes the myrtle beeches and towering mountain ash. It’s a world that feels ancient, and it is. But even this lush temperate rainforest is young compared to the forces that shaped Gippsland. To truly understand this landscape, one must step not centuries, but hundreds of millions of years into the past, to an age when Gippsland was not only far south of its current position, it was joined at the hip with Antarctica.

Welcome to the deep time of Gippsland. Long before the first Gunaikurnai families walked the hills, and millennia before European ships anchored at Port Albert, this land was forged in the cataclysms of supercontinent drift and the quiet work of rivers laying down sediments over eons. Its story begins not with people or even mammals, but with fire, ice, and the gradual break-up of a giant landmass called Gondwana.

Gondwana: Gippsland’s Earliest Origins

Roughly 180 million years ago, Australia did not exist as a separate continent. Instead, it formed the northeastern edge of Gondwana, a supercontinent that included present-day Africa, South America, India, Antarctica, and Australia. At that time, Gippsland sat much further south, near the Antarctic Circle. The climate, however, wasn’t as frigid as one might imagine. This was the Jurassic and early Cretaceous, an age of dinosaurs, greenhouse climates, and polar forests.

The earliest geological chapters of Gippsland’s story are etched in the deep rock layers of the Strzelecki Group, sediments laid down by braided rivers and ancient lakes between 145 and 100 million years ago. These rock beds, found throughout South Gippsland and inferred to underlie the Yarram-Port Albert region, record a time when the area was part of a rift valley forming between Australia and Antarctica.

As Gondwana slowly fractured, tectonic plates pulled apart. Cracks opened in the earth’s crust, creating elongated basins like the Latrobe and Gippsland Basins. These structural lowlands became repositories for vast amounts of sand, mud, plant debris, and volcanic ash. Each layer told a new story, and some would become the foundation for fossil fuel deposits millions of years later.

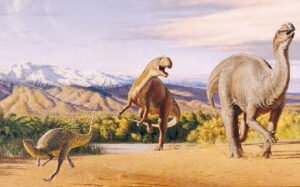

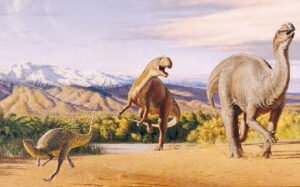

LEAELLYNASAURA, ALLOSAURUS & MUTTABURRASAURUS

A Polar Paradise?

LEAELLYNASAURA, ALLOSAURUS & MUTTABURRASAURUS

Imagine a land where the sun disappears for months, yet lush forests of conifers, ferns, and early flowering plants still thrive. That was Gippsland in the Early Cretaceous. Although situated within the polar circle, the region was far warmer than today’s poles, owing to higher global temperatures and the absence of polar ice caps.

The plants and animals that lived here had to adapt to long periods of twilight and cold winters. These adaptations would shape some of the most intriguing creatures ever to walk the Earth — Gippsland’s polar dinosaurs, which we’ll meet in detail in the next article. But the environment they inhabited was already taking on the look of home. Fern gullies, fast-flowing streams, thick undergrowth, the ancestors of Tarra-Bulga’s rainforest were already making an early appearance.

Nearby fossil beds, such as Koonwarra and Wonthaggi, preserve impressions of insects, fish, and feathers in exquisite detail. And while no dinosaur bones have been unearthed directly in Tarra-Bulga or Port Albert, the surrounding geological formations suggest they weren’t far away. The rivers that fed the ancient lakes may have flowed where the Tarra and Albert Rivers meander today.

Gippsland Basin: Australia’s Hidden Ocean

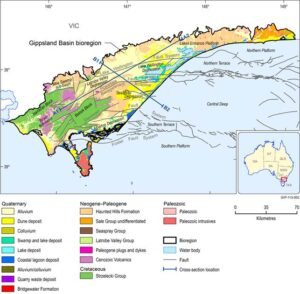

Geology of the Gippsland Basin bioregion including faults and structural elements. Locations of cross-sections A1-A2 and B1-B2 are delineated Data: Department of Environment and Primary Industries (Dataset 1)

As rifting intensified between 100 and 90 million years ago, the ancient rift valley of Gippsland was replaced by a developing shallow sea. Over time, the region transitioned from freshwater lake systems to swampy coastal plains and eventually to marine conditions. These changes were recorded in the sedimentary sequences of the Latrobe Group — a thick package of sandstones, siltstones, coal seams, and organic-rich shales.

These rocks are not only scientifically valuable – they are economically vital. During the mid-20th century, exploration in the offshore Gippsland Basin led to one of Australia’s largest oil and gas discoveries. Companies like Esso and BHP developed the Bass Strait oil fields, tapping into organic material buried during the Cretaceous and early Cenozoic periods.

Every barrel of oil pumped from Bass Strait, every whiff of gas heating a Melbourne home, originates from the swamps and forests that once covered prehistoric Gippsland. It’s a tangible reminder that fossil fuels are just that – fossils, the buried remains of life from deep time.

A Land in Motion

Gippsland’s story doesn’t end with the Cretaceous. As Australia separated fully from Antarctica and drifted north, the climate changed dramatically. Volcanic activity scarred the landscape. Massive river systems -ancestors of the Latrobe, Avon, and Thomson – carved new paths. And during the Ice Ages of the Pleistocene, sea levels fell, exposing land bridges across Bass Strait and reshaping the coastline we know today.

Yet beneath it all, the ancient structures remain. The same tectonic rift that once split Gondwana continues to influence the region’s geology. Earthquakes, coal seams, and the shape of the land all whisper of a prehistoric past.

Why It Matters

When we look out over Port Albert’s serene waters, walk beneath the moss-laden trees of Tarra-Bulga, or drive the winding roads near Yarram, we rarely imagine a landscape of volcanoes, rift valleys, and polar dinosaurs. But this is the deep time of Gippsland – a history not measured in generations, but in geologic epochs.

Understanding this history reshapes how we see the land. It reveals that Port Albert’s port is part of a story stretching back to ancient coastlines. That Yarram sits above the buried remnants of forests millions of years old. That Tarra-Bulga is more than a sanctuary- it’s a living echo of Gondwana.

And this is only the beginning. In the next chapter, we’ll descend into the forests of the Cretaceous, where dinosaurs adapted to darkness and life found a way — even in the polar night.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection