,The coinage of Australia encapsulates a rich narrative, charting the nation’s transition from a mosaic of colonial currencies to a unified modern economy. This journey reflects pivotal shifts in economic policies, technological advancements, and a deepening national identity. From the rudimentary use of foreign and makeshift currencies in the early settlement days, through the establishment of a national currency after Federation, to the sophisticated commemorative coins of today, each piece offers insights into the socio-economic and cultural epochs of Australia. As we delve into the detailed history of these metallic storytellers, we explore not only the evolution of currency but also the broader currents that have shaped Australia’s past and present. This article unfolds in five comprehensive sections, each illuminating a significant era in the development of Australian coinage.

Colonial Beginnings and Pre-Federation Coinage

In the nascent colony of New South Wales, the economic landscape was marked by a chaotic mix of foreign coins, each circulating at inconsistent values. This monetary confusion necessitated a robust response, leading to Governor Philip Gidley King’s 1800 proclamation that officially assigned fixed values to various foreign currencies, thus introducing some semblance of order to the economy.

In the nascent colony of New South Wales, the economic landscape was marked by a chaotic mix of foreign coins, each circulating at inconsistent values. This monetary confusion necessitated a robust response, leading to Governor Philip Gidley King’s 1800 proclamation that officially assigned fixed values to various foreign currencies, thus introducing some semblance of order to the economy.

Despite this measure, the scarcity of coins continued to hinder economic activity, compelling Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1813 to innovate with the Holey Dollar and Dump. By punching the center out of Spanish silver dollars, he effectively doubled the available currency, ingeniously curbing the shortage without depleting precious metal reserves. This temporary solution highlighted the colonies’ resourcefulness in the face of limited resources.

The introduction of British sterling coins in the 1820s marked a pivotal shift towards a more standardized monetary system. This transition not only facilitated smoother trade within the colonies and with international markets but also set the stage for economic stability and growth. It was during this period that the roots of a unified currency system began to take hold, gradually paving the way for the later establishment of a national currency.

The introduction of British sterling coins in the 1820s marked a pivotal shift towards a more standardized monetary system. This transition not only facilitated smoother trade within the colonies and with international markets but also set the stage for economic stability and growth. It was during this period that the roots of a unified currency system began to take hold, gradually paving the way for the later establishment of a national currency.

The pre-federation era of Australian coinage was characterized by a gradual move away from a reliance on makeshift and foreign coins towards a more organized and distinctly Australian system. This period saw the seeds of national identity being sown through the medium of currency, reflecting the colonies’ growing aspirations for economic independence and unity.

Through these early monetary policies and practices, the foundations were laid for the robust economic infrastructure that would support the federation of Australia. The coins from this era are not merely historical artifacts; they represent the tangible struggles and triumphs of a burgeoning nation striving to forge its identity and fiscal autonomy.

Federation and the Creation of a National Currency

The dawn of the 20th century brought with it the unification of Australia’s six colonies under the banner of federation, and with this political unity came the imperative for a unified currency. The introduction of the Australian pound, shilling & pence in 1910 was a decisive step towards solidifying national identity through currency. This initiative was spearheaded by the newly established Commonwealth government, which saw the creation of a national currency as essential to the economic integration of the disparate states.

The dawn of the 20th century brought with it the unification of Australia’s six colonies under the banner of federation, and with this political unity came the imperative for a unified currency. The introduction of the Australian pound, shilling & pence in 1910 was a decisive step towards solidifying national identity through currency. This initiative was spearheaded by the newly established Commonwealth government, which saw the creation of a national currency as essential to the economic integration of the disparate states.

Minting the new currency involved both practical and symbolic considerations. Coins were produced in denominations that ranged from the humble half-penny to the more substantial two shillings, or florin. These coins bore distinctive motifs that celebrated Australian flora and fauna, such as the kangaroo and the emu, skillfully incorporating elements of the national coat of arms. The choice of these symbols was deliberate, serving to foster a sense of national pride and unity.

The establishment of the Royal Australian Mint in 1965 in Canberra further centralized and streamlined the production of currency. This move underscored Australia’s growing economic autonomy from Britain, reflecting a broader desire for national self-determination that had been building since federation. The Mint became the sole producer of Australia’s coins, ensuring consistency in quality and design and heralding a new era of innovation in coin production.

The early years of the national currency also saw significant challenges. The Australian Pound was initially pegged to the British Pound, reflecting the lingering economic ties to the United Kingdom. However, global economic fluctuations and changes in silver prices eventually led Australia to adopt a decimal system, which aligned more closely with international standards and facilitated easier trade and economic management.

The creation of a national currency not only unified Australia’s economy but also played a critical role in shaping the country’s identity. The coins minted during this period were not merely tools of trade; they were emblems of a nation’s unity and a testament to its evolving sovereignty. These early coins, rich in symbolism and intent, laid the groundwork for the vibrant and diverse currency that Australians use today. They continue to be cherished as key artifacts of Australia’s historical narrative, encapsulating the spirit of an emerging nation on the cusp of a new century.

The Shift to Decimalization

The shift to decimalization in 1966 marked a defining moment in Australian monetary history, reflecting broader global economic trends and advancements in financial practices. This significant change transitioned Australia from the pounds, shillings, and pence system to a simpler, more intuitive system of dollars and cents. The decision was driven by the need to simplify calculations, improve economic efficiency, and align Australian currency more closely with international standards, many of which were already utilizing decimal systems.

The shift to decimalization in 1966 marked a defining moment in Australian monetary history, reflecting broader global economic trends and advancements in financial practices. This significant change transitioned Australia from the pounds, shillings, and pence system to a simpler, more intuitive system of dollars and cents. The decision was driven by the need to simplify calculations, improve economic efficiency, and align Australian currency more closely with international standards, many of which were already utilizing decimal systems.

The change was officially enacted on February 14, 1966, a day colloquially known as “C-Day” for Decimal Currency Day. The government implemented an extensive public education campaign to ease the transition, employing mass media strategies that included television and radio advertisements, informational booklets, and even catchy tunes to familiarize the public with the new currency. This massive educational effort was crucial in mitigating confusion and ensuring a smooth transition.

New denominations were introduced, including the one and two cent coins, and larger denominations up to the fifty cents, all minted in distinctive shapes and sizes to prevent errors in transactions. These coins featured native Australian wildlife, a thematic choice by Geoffrey Colley and Stuart Devlin, which emphasized Australia’s unique heritage and natural environment. This not only helped in promoting national identity but also in educating the public about Australia’s diverse fauna.

The shift also addressed practical economic concerns, such as reducing the cost of producing currency. The decimal system allowed for more straightforward financial transactions and was easier to adapt to electronic computing, which was gradually becoming more prevalent in banking and commerce. Moreover, this transition was part of a larger narrative of modernization and progress, symbolizing Australia’s readiness to participate more fully on the global stage.

The decimalization of the Australian currency system was not just a logistical update; it was a cultural shift that modernized the economy at a fundamental level. It reflected the nation’s capacity for change and adaptation, qualities that continue to define Australia’s approach to economic challenges and opportunities. The legacy of this transformation is evident today, as the decimal system remains a cornerstone of Australia’s financial infrastructure, supporting its dynamic economy and serving as a reminder of the country’s progressive strides in the mid-20th century.

Technological Innovations in Minting

Cultural Significance and Modern Developments

Australian coins do more than facilitate transactions; they are a canvas that reflects the nation’s cultural narratives and historical consciousness. Recent decades have seen the Royal Australian Mint focus on coins that not only serve an economic function but also engage the public with Australia’s rich heritage. Special editions and commemorative coins celebrate diverse themes from significant historical milestones to achievements in various fields, such as science, sports, and the arts, contributing to national pride and collective memory.

The introduction of new high-denomination coins, like the innovative $5 and $10 pieces, showcases advanced security features and intricate designs that narrate stories of Australia’s past and present. These coins often feature elements of indigenous art and culture, recognizing and honoring the deep history of the First Australians. Such inclusivity not only enriches the cultural value of these coins but also educates the public about the breadth of Australian history.

Moreover, these modern coins are instrumental in marking events of national significance, such as anniversaries of federation, landmark achievements, and royal commemorations, embedding a sense of time and place in their motifs. The coinage thus serves as a repository of collective memory, making history tangible and accessible to all Australians.

This approach not only enhances the aesthetic and collector value of Australian coins but also underscores their role in cultural education and national identity-building. Through their designs and themes, modern Australian coins continue to engage, inform, and inspire, bridging generations and celebrating the evolving story of a vibrant nation.

The narrative of Australian coinage encapsulates more than the economic and functional role of currency; it mirrors the cultural and historical evolution of the nation itself. From the early colonial period through to federation, and onto the modern era of decimalization and technological innovation, each coin tells a story of societal values, technological progress, and national identity. Australian coins, through their detailed designs and thematic diversity, invite exploration and reflection, offering a unique lens through which to view Australia’s rich historical tapestry. As we delve into the past through these metallic storytellers, we not only learn about economics or design but also engage with the broader currents that have shaped Australia into the vibrant, diverse nation it is today.

The Royal Australian Mint has continuously embraced cutting-edge technologies to refine the art and science of coin production. Among the standout achievements in its portfolio is the innovation seen in the $2 coin, introduced in 1988. This coin was particularly notable for its bi-metallic composition, combining copper, aluminium, and nickel to enhance durability and reduce wear. The design of the $2 coin is both culturally significant and artistically inspired, featuring the image of an Aboriginal tribal elder, a design based on the artwork by Ainslie Roberts which incorporates symbolic elements like the Southern Cross and native flora.

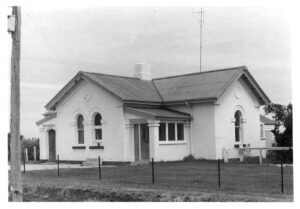

The Royal Australian Mint has continuously embraced cutting-edge technologies to refine the art and science of coin production. Among the standout achievements in its portfolio is the innovation seen in the $2 coin, introduced in 1988. This coin was particularly notable for its bi-metallic composition, combining copper, aluminium, and nickel to enhance durability and reduce wear. The design of the $2 coin is both culturally significant and artistically inspired, featuring the image of an Aboriginal tribal elder, a design based on the artwork by Ainslie Roberts which incorporates symbolic elements like the Southern Cross and native flora. Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection