Before sunrise, a cold mist drapes the Tarra River and Chinaman’s Point. It’s quiet now, but beneath this soil lies the story of one of Victoria’s most overlooked maritime communities—a story that archaeological evidence brought to light only in the last 30 years.

In the 1990s, archaeologists from La Trobe University excavated this unassuming headland and unearthed more than 29,000 artefacts: fire-blackened curing pits, rusted iron hooks, fragments of Chinese ceramics, opium tins, and thousands of fish bones. These remains revealed a sophisticated Chinese fish-curing operation that once thrived here in the late 1800s, supplying vital provisions to the Victorian goldfields.

This discovery challenges traditional narratives of Port Albert’s development, revealing that the town’s maritime economy wasn’t built by European settlers alone, but through a complex network of cultural exchange and commerce where Chinese entrepreneurs played a crucial but largely unacknowledged role.

Gateway to Gold: Port Albert as a Migration Hub

While Melbourne imposed strict regulations and poll taxes on Chinese arrivals in the 1850s, Port Albert offered a quieter alternative entry point for thousands of Chinese migrants heading to the goldfields at Ballarat, Bendigo, and Walhalla. Most arrived not as free agents but through a carefully organized credit-ticket system that shaped their economic opportunities and movements within the colony.

Under this arrangement, which had operated in China since the mid-1700s, merchants or headmen paid passage for individuals or groups who then became bound to work solely for their creditors until the debt was repaid. Historical records suggest that approximately 80% of Chinese people who traveled to Victoria during the gold rush did so under this system. As one Chinese merchant testified to an 1858 New South Wales select committee: when men signed such agreements, “the man who advances the money sends a head man with them and when they have paid back the money to him they can go back to China if they like; but if they do not clear the money they must dig.”

Under this arrangement, which had operated in China since the mid-1700s, merchants or headmen paid passage for individuals or groups who then became bound to work solely for their creditors until the debt was repaid. Historical records suggest that approximately 80% of Chinese people who traveled to Victoria during the gold rush did so under this system. As one Chinese merchant testified to an 1858 New South Wales select committee: when men signed such agreements, “the man who advances the money sends a head man with them and when they have paid back the money to him they can go back to China if they like; but if they do not clear the money they must dig.”

This invisible debt bondage system meant that while most Chinese arrivals ultimately aimed for the goldfields, they could be directed to other enterprises first—including fish-curing operations—if their sponsors demanded it. The indebted workers typically received basic rations, accommodation, and possibly a small wage, but the profits of their labor went to their creditors until the passage debt, plus interest, was repaid—a process that often took several years.

Port traffic peaked during the gold rush years, briefly rivalling Melbourne’s, especially for the movement of cattle and goldfield supplies. Historical records indicate that Chinese migrants often chose Port Albert to avoid the poll taxes imposed at larger ports, creating an informal network of entry points along Victoria’s coastline.

Chinese passengers would disembark from coastal vessels at Port Albert’s wharves, often having travelled via intermediate ports in Tasmania, then continue inland on foot or by cart. Many walked more than 200 kilometres to reach the Walhalla diggings, establishing temporary settlements near Tarraville and along the trails. Archaeological surveys have uncovered evidence of roadside shrines and rest camps along these routes.

This human movement transformed the sleepy fishing town into a vital logistical hub. More travellers meant increased demand for accommodation, fresh water, food supplies, and transport services. While many Chinese migrants passed through quickly, their presence stimulated local trade and connected Port Albert to global commercial networks spanning Tasmania, Hong Kong, and southern China.

Building a Maritime Economy: The Fish-Curing Industry

While many Chinese continued inland, others recognised opportunity in Port Albert’s abundant marine resources and established a fish-curing industry along the eastern shoreline at what became known as Chinaman’s Point.

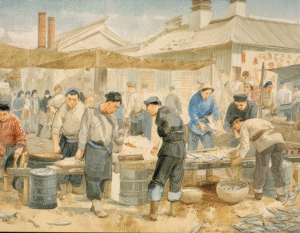

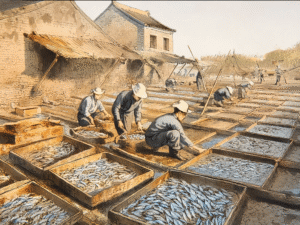

The operation was deceptively sophisticated. Chinese curers purchased fresh catch directly from local European fishermen, then processed it through a labour-intensive method of gutting, salting, and sun-drying. The fish—predominantly mullet, garfish, and flounder—were laid out on timber racks and carefully tended to ensure proper preservation. Once cured, they were bundled tightly in wicker baskets, insulated with wet ferns (and later, ice), and transported to miners on the goldfields.

The curing process transformed highly perishable fish into a stable commodity that could last for weeks, making it ideal for cart journeys inland. Archaeological evidence from the Chinaman’s Point excavation conducted by La Trobe University researchers suggests industrial-scale production—with thousands of fish bones, multiple curing pits, and extensive rack foundations indicating a substantial operation.

The curing process transformed highly perishable fish into a stable commodity that could last for weeks, making it ideal for cart journeys inland. Archaeological evidence from the Chinaman’s Point excavation conducted by La Trobe University researchers suggests industrial-scale production—with thousands of fish bones, multiple curing pits, and extensive rack foundations indicating a substantial operation.

This created a reliable secondary market for local fishers, who could sell directly to Chinese processors rather than depending solely on inconsistent Melbourne buyers. By 1860, records show Port Albert had over thirty vessels regularly engaged in commercial fishing and transport between Gippsland and Tasmania.

The trade didn’t just support the curers and fishers but generated work for port agents, basket weavers, ice vendors, and cart drivers. Chinese buyers sometimes paid with gold dust or imported goods including tea, silks, and medicinal herbs, creating complex exchange networks that extended well beyond simple cash transactions.

Salt, Fish, and Gold: Feeding the Colonial Economy

As thousands of Chinese miners laboured in Victoria’s goldfields, they relied on cultural staples—rice, tea, and dried fish—to sustain them through gruelling work. Much of that preserved fish came from the curing sheds at Port Albert, creating a supply chain that stretched from the coast to the gold-rich hills of central Victoria.

Local families like the Averys and Gouldens developed mutually beneficial trading relationships with Chinese buyers, who provided stable income during periods when Melbourne markets were inaccessible due to weather or changing demand. The fish trade helped many local families “stay afloat, quite literally,” as one descendant later recalled.

The industry’s scale became substantial enough to justify significant infrastructure. By the 1870s, Port Albert had established ice storage facilities and dedicated transport arrangements specifically for the fish trade. In 1894, ice was purchased for £1 15s per ton and carted from Palmerston station to the Ice House at the wharf, demonstrating the economic importance of preserving the catch.

Port Albert’s role in this trade elevated it beyond a simple fishing village—it became a key link in a colonial provisioning network that helped fuel Victoria’s gold boom. The dried fish nourished not just hunger but an entire economy built on extraction and expansion.

Exclusion and Resilience: Navigating Colonial Society

Despite their economic contribution, Chinese fishermen faced systematic exclusion—not through direct prohibition, but through bureaucratic barriers and institutional prejudice that gradually eroded their position in the industry.

The 1859 Fisheries Act and subsequent regulations required fishers to register their names, residences, and net storage locations—administrative hurdles for those with limited English and uncertain legal status. When the Port Albert branch of the Victorian Fishermen’s Union formed in 1889, its rules gave members exclusive access to cold storage, ice, and union-backed sales networks, yet no Chinese names appear in its early membership rolls.

While these regulations weren’t explicitly racial in language, they functioned as effective barriers to Chinese participation in the increasingly formalized fishing economy. Union rulebooks from the period show how membership restrictions and institutional practices worked to exclude non-European fishermen without directly naming them.

Without leases, legal protection, or political representation, Chinese operators remained in precarious positions—tolerated for their economic utility but denied the security afforded to their European counterparts. Still, they demonstrated remarkable adaptability, maintaining operations at Chinaman’s Point for decades despite these constraints.

Fading Tides: The Decline of Chinese Fishing

By the early 1900s, the once-busy curing operations had fallen silent. Multiple factors drove this decline: environmental degradation from decades of intensive fishing had devastated local oyster beds, while estuaries around Corner Inlet began silting up due to upstream land clearing and erosion.

Simultaneously, larger ports like Lakes Entrance and Port Welshpool gained prominence, drawing infrastructure investment away from Port Albert. Tightening immigration restrictions under the White Australia Policy further constrained the movement of Chinese workers and merchants who might have maintained the trade.

Rising union power and regulatory frameworks made it increasingly difficult for Chinese operators to access essential services like wharves, ice, and transport. What remained was infrastructure shaped by their presence—fish sheds, trade routes, and practices adopted by others—but the people themselves faded from view, absent from the records and overlooked in local histories.

Not all Chinese workers left, however. Some who had been unsuccessful on the goldfields returned to coastal areas like Port Albert to work in fish curing or market gardening—particularly those who still needed to earn money to pay off their passage debts. These individuals occupied an economic middle ground, neither fully integrated into the European fishing community nor able to establish their own independent enterprises under increasingly restrictive conditions.

Not all Chinese workers left, however. Some who had been unsuccessful on the goldfields returned to coastal areas like Port Albert to work in fish curing or market gardening—particularly those who still needed to earn money to pay off their passage debts. These individuals occupied an economic middle ground, neither fully integrated into the European fishing community nor able to establish their own independent enterprises under increasingly restrictive conditions.

The disappearance wasn’t just physical but historiographical. Their story vanished not once but twice—first from the landscape, then from our collective memory of it. This pattern of historical erasure reflects broader trends in Australian maritime history, where non-European contributions were often overlooked in official narratives.

Excavating Memory: Reclaiming a Multicultural Past

Today, there are few visible markers of the Chinese presence in Port Albert—no statues or street names, no heritage plaques where the curing sheds once stood. Yet their contribution lingers in the town’s economic foundations, infrastructure, and maritime heritage.

The archaeological work at Chinaman’s Point represents more than academic interest; it offers an opportunity to reclaim a more inclusive understanding of Australian coastal history. The thousands of artefacts recovered—hooks, bowls, fish bones, opium tins—provide tangible connections to lives otherwise erased from historical accounts.

Recently, this has begun to change. An exhibit at the Port Albert Maritime Museum includes findings from the Chinaman’s Point excavation, while discussions have explored possibilities for heritage trails, interpretive signage, and digital storytelling projects to acknowledge the multicultural dimensions of Gippsland’s past.

Restoring these memories isn’t simply about filling historical gaps. It’s about recognizing whose labor helped build the foundations of Port Albert—and giving that story a place not only in archives but in how we understand Australian maritime heritage today. The recent efforts to include this history in museum displays represent important steps toward a more inclusive narrative.

The Chinese fishermen of Port Albert left no monuments, and few recorded names. But they salted the fish, stoked the fires, and sustained a colony hungry for gold and growth. Their story reminds us that Australia’s maritime heritage was shaped not by a single cultural tradition, but through complex connections between peoples and places—quiet hands working over curing racks at dawn, whose legacy still rises with each tide.

Fascinating Fact #1

More than 29,000 artefacts were recovered at Chinaman’s Point, including hooks, bowls, fish bones, and remnants of drying racks—offering rare insight into Chinese maritime life in colonial Victoria.

Fascinating Fact #2

- By 1856, Port Albert had over 30 vessels regularly transporting passengers, livestock, and supplies between Gippsland and Tasmania.

- Port traffic peaked in the gold rush years, briefly rivalling Melbourne’s, especially for movement of cattle and goldfield supplies.

- Chinese migrants were known to walk more than 200 km from Port Albert to reach Walhalla, avoiding poll taxes imposed at larger ports.

- Temporary Chinese settlements emerged near Tarraville and along the track to the diggings, with some evidence of roadside shrines and rest camps.

Fascinating Fact #3

- Fish were packed in 50 lb wicker baskets, insulated with wet ferns, and later, with ice.

- In 1894, ice was purchased for £1 15s per ton and carted from Palmerston station to the Ice House at the wharf.

- Chinese fish curers operated on a scale large enough to justify the construction of fish sheds and drying racks along the shoreline.

- Local families like the Averys and Gouldens often sold directly to Chinese buyers—creating a mutually beneficial trade partnership.

Fascinating Fact #4

- Chinese buyers sometimes paid with gold dust or imported goods, including tea, silks, and medicinal herbs.

- Bundled dried fish from Port Albert was packed in grass matting or rice-straw wrapping for transport to inland goldfields.

- The fish trade supported not only the curers and fishers, but also port agents, cart drivers, basket weavers, and ice vendors.

- Archaeological digs uncovered bones of estuarine species typical of those salted for goldfield use—linking the site directly to inland trade.

Legal Note

- The 1859 Fisheries Act and 1864 net size regulations set strict controls on commercial fishing practices.

- Professional fishers had to register their name, place of residence, and net storage locations—barriers for non-English speakers.

- Union rulebooks banned members from working with, or even selling ice to, non-members—effectively excluding Chinese fishers.

- No Chinese individuals are recorded in union meeting minutes, despite their visible presence at Chinaman’s Point.

Environmental Context

- The native flat oyster (Ostrea angasi) was virtually wiped out by the 1870s, collapsing one of Port Albert’s key fisheries.

- Chinese curing sheds disappeared from maps and photos by the 1910s, with little mention in local newspapers or government reports.

- Silting from land clearing and sediment runoff choked the channels once used by fishing boats.

- Port Albert’s trade declined overall after the rail line and port facilities shifted inland, bypassing the once-busy wharves.

© Port Albert Maritime Museum, 2025.

This article may be shared, reproduced, or quoted in part or full for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution is given. Please credit:

Port Albert Maritime Museum and include a link to our website and Facebook page:

🔗 portalbertmaritimemuseum.com.au

🔗 facebook.com/portalbertmaritimemuseum

For commercial use or media inquiries, please contact the museum directly.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection