In the quiet tidal flats of Corner Inlet, beneath layers of silt and time, lie the traces of an extraordinary abundance. Long before steamers plied the coast and colonial appetites reached southward from Melbourne, these waters were lined with living reefs of native flat oysters—Ostrea angasi—anchored in muddy beds and clustered across the estuarine floor in complex, self-sustaining systems. These oysters shaped not only the ecology of the inlet, but also the rhythms of human life along its shores.

To the Gunaikurnai people, they were a source of food, trade, and ceremony—harvested sustainably for thousands of years, their shells layered in ancient middens still visible today. To colonial settlers, arriving in the 1840s, they represented something else entirely: an economic opportunity ripe for the taking.

What followed in Port Albert and Corner Inlet was a strikingly modern story told in a 19th-century key—a tale of extraction without restraint, of infrastructure built on the promise of endless supply, and of collapse so swift it shocked even those who had profited most from it. Within little more than a decade, one of the richest shellfish ecosystems in southern Australia had been all but obliterated.

This is not just a history of oysters. It is a story about our understanding of abundance, our failure to recognise ecological thresholds, and the long shadow cast when a resource is reduced to a commodity.

Colonial Appetite and the Oyster Boom

By the mid-1840s, Melbourne was a town awakening to its own colonial ambitions. Paved with gold-rush aspirations and fuelled by a swelling population, its appetite extended well beyond bricks and ballast. In the taverns and saloons of Little Lonsdale Street, oysters emerged as a fashionable indulgence—both working-class fare and middle-class delicacy. They were sold by the dozen at dedicated oyster bars, hawked from baskets on street corners, and served stewed or raw alongside stout in brothels and billiard rooms.

This sudden craving was met with a natural bounty few settlers had expected. Boats arriving from Corner Inlet—particularly Port Albert—were soon landing loads of native flat oysters in quantities that astonished the market. Historical accounts describe early vessels bringing 400 to 500 dozen at a time, often multiple times per week. The Lucy, a small cutter running between Port Albert and Melbourne from 1844, was among the first to establish a profitable trade in oysters alone.

Contemporary reports described the fishery as “more lucrative than fishing”—a telling distinction. While fishing required nets, skill, and patience, oysters needed only a dredge, a rope, and a boat with a shallow draft. The extraction was simple. The profit margins were extraordinary.

At the height of the boom in 1860, shipments from Port Albert alone were valued at £3,000—an immense figure in colonial currency. For comparison, a skilled tradesman might earn £100–150 annually. This single year’s harvest from one inlet represented the equivalent of two decades of wages for most labourers. The oyster had become, almost overnight, the cornerstone of an emergent colonial luxury economy.

But as with so many colonial industries, its success was built on a fragile and misunderstood foundation.

The Shellfish That Built a Port

In its 1860s heyday, oysters made up an estimated 60–80% of Port Albert’s entire seafood industry. Though the boom was short-lived, the impact was profound. The demand for native flat oysters (Ostrea angasi) drove a wave of investment in boats, jetties, trade routes, and ultimately helped justify the extension of the railway into South Gippsland. At its peak, the oyster trade generated £3,000 a year — the modern wage equivalent of over $2.55 million AUD — making it one of the region’s most lucrative natural industries. While overfishing and silting led to collapse within just a few years, the infrastructure it spawned shaped the town’s economic future for decades.

Oysters and Brothels: A Taste of 19th-Century Melbourne

In 1850s Melbourne, oysters were more than a culinary delicacy — they were a staple of the city’s underground nightlife. Historical accounts and illustrations from the era reveal that oyster saloons proliferated in the laneways of Little Lonsdale Street and surrounding the Eastern Market, areas also known for housing some of the city’s most notorious brothels. These establishments often served oysters alongside champagne and other aphrodisiacs, catering to the appetites of gold rush-era patrons.

Oysters dredged from Port Albert and Western Port were ferried in by the thousands each week, feeding a booming demand. In 1843 alone, over 2,900 dozen oysters were shipped from Port Albert to Melbourne and sold at two shillings a dozen — a luxury item at the time. Their popularity in Melbourne’s sex trade milieu was such that the phrase “oysters and a lady” became colloquial shorthand for indulgent — and illicit — entertainment.

Techniques of Extraction: From Sail to Steam

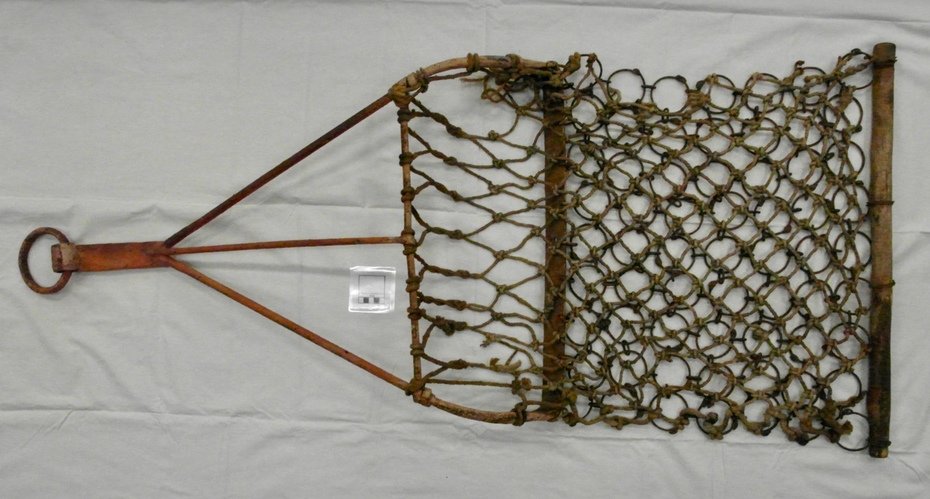

The tools of the early oyster fishery were deceptively simple, their impact anything but. Dredging—a method imported from British and American oyster grounds—was quickly adapted to the calm, shallow estuaries of Corner Inlet. The earliest dredges were triangular iron frames fitted with a scraping edge or “knife” along the base. Behind this, a strong net or iron-ringed bag trailed along the seafloor, scooping oysters as the blade dislodged them from their muddy beds.

These dredges were deployed from small sailing vessels—open cutters and smacks like the Elsinore, a 42-ton schooner that worked the beds offshore from Port Albert in the 1880s. Without steam winches, the dredge bags had to be hauled aboard by hand—a backbreaking task when the catch was good and the tide working against the sails. Yet even this labour-intensive method yielded impressive volumes, and soon the waters were crowded with boats.

Mechanisation arrived in the form of the Amy, a 53-ton steam vessel capable of hauling multiple dredges simultaneously. Her engine throbbed as she steamed out of the inlet, dragging iron across reef and mud. Aboard, a government official once observed the dredging firsthand: spars swung out from the mast, four dredges lowered two to a side, the ropes reeled in by steam-powered winch. The deck was soon piled with oysters—but also scallops, starfish, sea sponges, zebra-striped reef fish, and the occasional porcupine fish or octopus.

While the oysters were sorted into barrels, debris and creatures bearing spat were sometimes returned to the sea—a rudimentary form of stewardship. But the damage had already been done. The dredge blades tore not just individual oysters but the very reef structures they relied upon. Each pass scraped away habitat, undermining the conditions needed for recovery.

The technology had made the harvest faster. But it had also made collapse inevitable.

Collapse: Twelve Years to Devastation

The collapse came quickly—astonishingly so. Between 1842 and 1854, the oyster beds of Corner Inlet and Port Albert shifted from abundance to exhaustion. What had been marketed as a limitless natural resource was, in truth, a fragile ecological structure—vulnerable to overharvest, sedimentation, and the very tools designed to extract it.

By the mid-1850s, the beds of Western Port, similarly rich in native flat oysters, had already been stripped beyond commercial use. Boats from that region relocated to Corner Inlet, intensifying pressure on an already stressed system. The convergence of fleets, driven by Melbourne’s insatiable demand, quickly pushed the region’s oyster population beyond its tipping point.

The Gippsland Times, writing in February 1862, admitted what many already knew: “Some years must elapse before the oyster beds in this neighbourhood will recover from the excessive working it underwent in 1860.” That year, upwards of £3,000 worth of oysters were shipped from Port Albert alone. The boom had reached its zenith—and its ruin.

Colonial authorities responded with legislation. The Oyster Act of 1859 was Victoria’s first fisheries law, introducing basic regulations to protect what remained. It restricted the season to four months per year and imposed a minimum legal size—oysters had to exceed the circumference of a crown piece (38.5 mm) to be legally taken. All harvesting now required a government-issued licence.

But far from equitable, the Act enshrined exclusion. For Indigenous communities—particularly Gunaikurnai and Boon Wurrung women, who had gathered oysters for millennia—there was no pathway to obtain a permit. The new legal framework turned traditional harvest into criminal offence, pushing Indigenous presence out of a fishery they had maintained sustainably for generations.

Meanwhile, the regulations proved too little, too late for the ecosystem itself. Oyster reefs—unlike beds of fish—are built organisms. Their physical structure creates the very conditions oysters need to breed and thrive. Once those structures were dredged apart, their biological and environmental function collapsed. Without reef, there could be no spat settlement. Without spat, no future generations.

By the early 1860s, the once-prolific Ostrea angasi reefs of Corner Inlet had all but vanished. What remained were ghost beds: broken shell, silted sediment, and the memory of an abundance that seemed, for a moment, infinite.

First Peoples and the Criminalisation of Custodianship

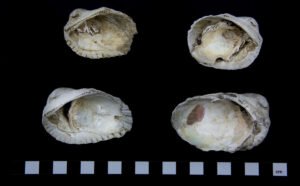

Long before the oyster saloons of Melbourne or the dredges of Port Albert, the tidal waters of Corner Inlet nourished the Gunaikurnai people. Along the shores of Nooramunga and Snake Island, shell middens rise like quiet monuments—layered with Ostrea angasi, spindle shell, mud cockle, pipi, mussel, and triton. These deposits speak of thousands of years of sustainable harvesting: shellfish collected seasonally, shared communally, and integrated into the cultural, spiritual, and ecological rhythms of Country.

To harvest oysters was not merely to collect food—it was to participate in a living relationship with place. The reefs were not resources, but kin: part of a system of reciprocity and respect. Indigenous harvesting, shaped by careful timing and ecological observation, maintained these shellfish populations over countless generations.

That custodianship was severed almost immediately upon colonisation. In 1841, the colonial government passed legislation explicitly banning First Nations from harvesting shellfish in the areas now serving Melbourne’s growing demand. This act formalised what would become a long pattern of exclusion: the redefinition of Indigenous subsistence as trespass.

The passage of the Oyster Act in 1859 deepened this rupture. By requiring a Crown licence to harvest oysters, it transformed cultural practice into criminality. There was no mechanism for Gunaikurnai families to obtain such permits, no recognition of pre-existing rights. What had been ceremony, survival, and stewardship became, overnight, illegal activity.

This legal erasure had more than economic consequences. It ruptured intergenerational knowledge transfer, broke links between people and place, and imposed silence where once there was cultural expression. The same Act that aimed to protect oyster populations after colonial overharvesting had devastated them, effectively extinguished Indigenous access to the shellfish that had sustained them for millennia.

1841 and the Legal Erasure of Indigenous Harvest Rights

The 1841 ban on First Nations harvesting shellfish wasn’t simply a matter of regulation—it was an early assertion of Crown authority over land and sea, grounded in the legal fiction of terra nullius. At the time, Victoria was still the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and the colonial government did not recognise that Aboriginal people had any pre-existing rights to territory, resources, or customary law. In this legal vacuum, all land and coastal waters were treated as Crown property. As oyster beds gained commercial value, their use was restricted to those granted access by the state—typically settler men. Indigenous women, whose shellfish gathering had sustained communities for millennia, were now trespassers on their own Country. The law did not acknowledge their sovereignty, their stewardship, or even their presence.

Revival Attempts and Scientific Blind Spots

The collapse of the oyster beds in Corner Inlet and Port Albert did not go unnoticed by colonial officials or scientists. By the 1880s, faced with depleted natural stocks and rising market pressure, efforts turned toward artificial cultivation and fishery reform. But what followed was a cycle of hopeful experimentation—and repeated failure—driven by a poor understanding of how oyster ecosystems actually functioned.

Among the most prominent voices was William Saville-Kent, a respected British-born fisheries scientist whose 1887 survey of Port Albert’s oyster grounds sounded an urgent alarm. The remaining reefs, he reported, were “on the verge of ruin”—smothered by sediment, parasitic overgrowths, and relentless poaching. He proposed the establishment of a government oyster reserve near Chair Beacon: a fenced, two-acre bed stocked with brood oysters and monitored by a full-time caretaker. The idea was forward-thinking, even visionary for its time.

But execution fell short. One experimental bed was laid on copper wire, which leached toxins and killed both juvenile and adult oysters. Others were enclosed by stakes or fencing that obstructed tidal flows, leading to siltation and stagnation. Despite government investment and more than 120 fisheries regulations issued between 1859 and 1930, the underlying ecological problem was never resolved.

The colonists failed to grasp that oyster reefs were not just resources—they were infrastructure. These reefs created the very conditions oysters needed to thrive: clean, hard substrate for spat settlement; protection from currents; filtration of water. Once dredging destroyed the reef’s structure, simply transplanting shellfish or closing seasons was not enough.

It would take more than half a century—and the lens of modern ecology—for scientists to understand that without the reef, there is no recovery. In this, the failed revival attempts of the 19th century offer not just cautionary tales, but essential lessons in humility: ecosystems are not machines, and abundance cannot be engineered once its foundation has been broken.

Infrastructure of Exploitation: Wharves and Railways

The oyster boom did not just reshape the seafloor—it helped shape the colonial map. As early as 1846, entrepreneur Robert Turnbull constructed the first jetty at Port Albert, charging a penny per sheep and a shilling per head of cattle. By the 1850s, the site had grown into a working government wharf, complete with gauging stations, a customs house, and goods sheds. The town, once little more than a natural harbour, was becoming a linchpin in Victoria’s coastal trade network.

The oyster boom did not just reshape the seafloor—it helped shape the colonial map. As early as 1846, entrepreneur Robert Turnbull constructed the first jetty at Port Albert, charging a penny per sheep and a shilling per head of cattle. By the 1850s, the site had grown into a working government wharf, complete with gauging stations, a customs house, and goods sheds. The town, once little more than a natural harbour, was becoming a linchpin in Victoria’s coastal trade network.

Oysters were among the earliest and most profitable commodities to move across this infrastructure. Their durable shells and perishable interiors made them ideal candidates for rapid, high-volume transport—but only if speed could be assured. In the 1860s and ’70s, oysters were still shipped by steamer and horseback relay. But spoilage was common, and Melbourne’s demand was growing impatient.

The answer came with the railways. In 1879, the line reached Sale; by 1892, it extended to Palmerston, just kilometres from Port Albert. Iced seafood—oysters, shark, snapper, and flounder—could now reach Melbourne’s markets in a matter of hours. Newspaper reports from the 1880s describe baskets of fish and shellfish being loaded by the hundred each week. The port was no longer just a local hub; it was a node in a growing colonial export economy.

The answer came with the railways. In 1879, the line reached Sale; by 1892, it extended to Palmerston, just kilometres from Port Albert. Iced seafood—oysters, shark, snapper, and flounder—could now reach Melbourne’s markets in a matter of hours. Newspaper reports from the 1880s describe baskets of fish and shellfish being loaded by the hundred each week. The port was no longer just a local hub; it was a node in a growing colonial export economy.

But this efficiency had a cost. The faster oysters could be sold, the more incentive there was to dredge harder and deeper. Rail made commercial overharvest economically viable. As with so many colonial industries—timber, gold, wool—the infrastructure that sustained growth also hastened collapse.

The Port Albert wharf, extended and reinforced over decades, remains today as a weathered monument not just to commerce, but to the speed at which abundance can be transformed into absence—when nature is made to fit the rhythm of markets.

Legacy and Lessons: Toward Restoration

Today, more than a century after the last oyster dredges fell silent in Port Albert, the reefs they once harvested are largely gone. What remains are scattered clumps of Ostrea angasi—isolated individuals clinging to mudbanks and channel edges, the survivors of an ecosystem reduced by over 95% since European settlement. The vast, reef-forming communities that once filtered water, stabilised shorelines, and sheltered countless marine species are now considered functionally extinct.

For decades, this loss went unnoticed. Oyster reefs, unlike forests or wetlands, left few visible scars above water. Yet their disappearance has had profound consequences: declines in water quality, erosion of marine biodiversity, and the silencing of an ecological function that once operated at landscape scale.

In recent years, however, a shift has begun. Restoration efforts across Australia—from Noosa to Port Phillip Bay—are drawing on historical baselines to rebuild what was lost. Scientists are turning to old shipping records, colonial fisheries data, and even shell middens to map where reefs once flourished. Projects no longer focus solely on restocking oysters, but on rebuilding the reef structure itself: placing limestone, recycled shell, or rock to recreate the hard surfaces essential for spat settlement and reef formation.

This approach marks a return to first principles—recognising that ecosystems are communities, not commodities. And it opens the door for deeper partnerships, particularly with Indigenous custodians whose knowledge of these places stretches far beyond the colonial record.

The story of Port Albert’s oysters is not just a tale of loss. It is a mirror held up to our relationship with the natural world—a reminder that abundance is not inevitable, that extraction has limits, and that healing, while slow, is possible.

Restoration is no longer just a scientific ambition. It is an act of historical recognition. And, perhaps, a gesture of ecological repair.

In the end, the oysters of Port Albert offer more than a story of colonial industry or ecological collapse. They remind us how easily abundance can be mistaken for permanence, and how quickly knowledge—both scientific and cultural—can be cast aside in pursuit of profit. Yet in their shells, scattered across tidal flats and buried in middens, lies the memory of a different way of living with place. If we are to restore what was lost, it will not be through technology alone, but through remembering how to listen—to the land, the sea, and those who have always known their rhythms.

Flat-Out Fascinating: Fun Facts About Native Oysters

Ostrea angasi, the native flat oyster once dredged from Port Albert’s muddy estuaries, is as biologically intriguing as it is historically significant. These oysters are protandric hermaphrodites — meaning they typically begin life as males and later change sex to female. Some may even switch back again, depending on environmental conditions and population dynamics.

Ostrea angasi, the native flat oyster once dredged from Port Albert’s muddy estuaries, is as biologically intriguing as it is historically significant. These oysters are protandric hermaphrodites — meaning they typically begin life as males and later change sex to female. Some may even switch back again, depending on environmental conditions and population dynamics.

Unlike Sydney rock oysters, O. angasi prefers cooler, subtidal habitats and can grow up to 18 cm across, making them one of Australia’s largest edible oysters. During the 1850s, Port Albert was a major export hub, with boats reportedly sending up to 14,000 dozen oysters a week to Melbourne’s marketsOysters and mussels are….

Oysters filter vast amounts of water — a single adult can clean over 100 litres a day, helping maintain healthy estuarine ecosystems. Though functionally extinct in the wild, efforts are underway to restore O. angasi reefs and their ecological role in Australian waters.

© Port Albert Maritime Museum 2025. All rights reserved. May be reproduced with acknowledgement and a link to the museum’s website or Facebook Page.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection