TL;DR

Gippsland was once home to small, feathered polar dinosaurs like Leaellynasaura and Qantassaurus, adapted to months of darkness and icy winters near the ancient South Pole. Fossil evidence from the Strzelecki Group reveals a thriving ecosystem of herding herbivores, fast-moving predators, and early birds — making Gippsland one of the most unique Cretaceous habitats on Earth.

Life in Cretaceous Gippsland, When Dinosaurs Roamed the Polar Forests

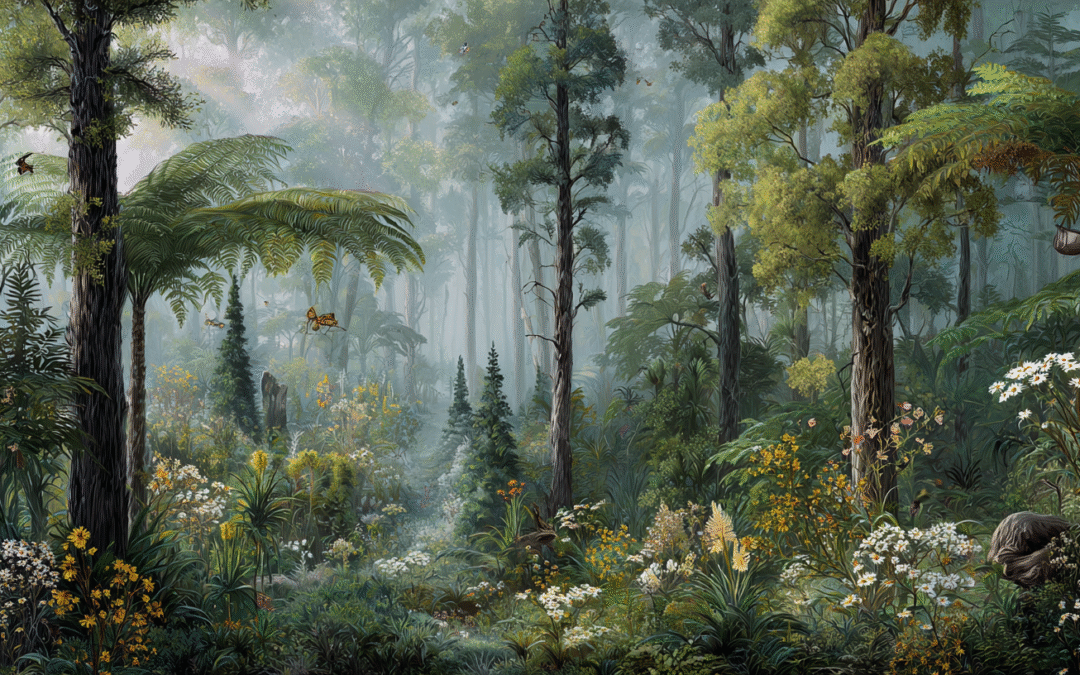

The forest is silent. Not with the stillness of sleep, but the suspenseful hush before movement, the crack of twig underfoot, the rustle of something unseen. A pair of wide eyes gleams under a canopy of ancient tree ferns. A feathery silhouette darts through the polar undergrowth. It is not a bird, not yet. It is Leaellynasaura, a dinosaur adapted to months of twilight in a world both familiar and alien, the polar forests of ancient Gippsland.

The forest is silent. Not with the stillness of sleep, but the suspenseful hush before movement, the crack of twig underfoot, the rustle of something unseen. A pair of wide eyes gleams under a canopy of ancient tree ferns. A feathery silhouette darts through the polar undergrowth. It is not a bird, not yet. It is Leaellynasaura, a dinosaur adapted to months of twilight in a world both familiar and alien, the polar forests of ancient Gippsland.

Dinosaurs of the Southern Lights

Roughly 115 to 100 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous, the region we now know as Gippsland lay within the polar circle, connected to Antarctica, deep in Gondwana’s southern realm. Yet, despite long winters of darkness and relatively cool temperatures, this landscape hosted a thriving ecosystem of dinosaurs uniquely adapted to life without sunshine.

These weren’t the thunderous giants of Hollywood films. The dinosaurs of ancient Victoria, and likely Gippsland, were mostly small, fast, and agile. They moved in packs, possibly nested in burrows, and some may have sported downy feathers for warmth.

Leaellynasaura: The Forest Runner

One of the most iconic of these southern dinosaurs is Leaellynasaura amicagraphica, a name that honours the daughter of two paleontologists and means “friendly graphic.” Fossils of this tiny herbivore, barely 1.5 metres from nose to tail, were first discovered at Dinosaur Cove, west of Gippsland, but it almost certainly ranged across the then-continuous coastal forests, including what is now the Yarram and Tarra-Bulga region.

One of the most iconic of these southern dinosaurs is Leaellynasaura amicagraphica, a name that honours the daughter of two paleontologists and means “friendly graphic.” Fossils of this tiny herbivore, barely 1.5 metres from nose to tail, were first discovered at Dinosaur Cove, west of Gippsland, but it almost certainly ranged across the then-continuous coastal forests, including what is now the Yarram and Tarra-Bulga region.

What makes Leaellynasaura extraordinary is not just its size, but its eyes and tail. With enormous optic lobes in its brain and unusually large eye sockets, it may have seen well in near-darkness. Some scientists believe it was capable of being active year-round, even in the months-long darkness of polar winter, a rare trait among dinosaurs.

Its tail, more than twice the length of its body, was stiffened by tendons and likely served for balance and social display. Imagine a small, feathered creature bounding through undergrowth, tail streaming behind, alert to danger.

Qantassaurus and the Ornithopod Herds

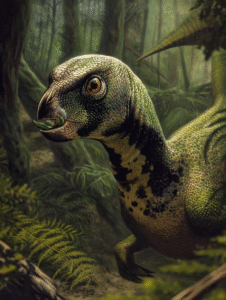

Qantassaurus intrepidus (Artist’s impression)

Alongside Leaellynasaura lived Qantassaurus intrepidus, another small herbivore whose name nods to the national airline that transported the dig team. Discovered near Inverloch, this stout, bipedal dinosaur had powerful hind legs, likely allowing it to run from predators in short bursts.

Together with other ornithopods like Galleonosaurus, these dinosaurs may have travelled in herds, using collective vigilance to detect threats in the dim forest light. They browsed on ferns, clubmosses, and the early flowering plants emerging in the Cretaceous.

In a land where sunlight vanished for months at a time, survival depended on more than just sharp senses, it demanded social behaviour, seasonal migration, and perhaps even the ability to hibernate. Some paleontologists suggest these animals may have slowed their metabolism during the long winter, much like today’s reptiles or bears.

Carnivores in the Shadows

But where there are plant-eaters, there are predators.

Recent discoveries from Victoria’s southern coast hint at the presence of fierce carnivorous dinosaurs in these ecosystems, some of them previously unknown in the region. These include:

Megaraptorids (artists impression)

Megaraptorids: Large, clawed predators with powerful forelimbs. Fossil remains of the oldest known megaraptorid were recently found in Victoria, indicating their deep evolutionary roots.

- Unenlagiines: Agile, feathered theropods related to the dromaeosaurs (the “raptor” family). These likely hunted small prey through speed and cunning.

- Carcharodontosaurs: Massive, sharp-toothed predators similar to Allosaurus, now known to have roamed parts of southeastern Australia. Their presence suggests a complex food web with apex predators.

While no complete skeletons have yet been found in the Gippsland region, the geological continuity of the Wonthaggi and Strzelecki formations suggests these same species or their relatives were present here too.

Imagine a forest shrouded in mist, a Leaellynasaura herd pauses at a stream, unaware of the claws waiting in the underbrush.

Dinosaurs by Starlight

Living within the polar circle meant experiencing long winters without sunrise. How these dinosaurs coped remains one of Australia’s great paleontological mysteries.

Galleonosaurus (Artist’s interpretation)

Some researchers propose that smaller species may have migrated north during the coldest months, while others may have stayed put, relying on insulated feathers and flexible diets. Large eyes and heightened sensory awareness were likely essential for survival.

This ability to live, even thrive, in polar environments sets Australian dinosaurs apart. Globally, most dinosaur fossil sites lie in warm, temperate, or tropical zones. But Gippsland’s record, and that of southern Victoria, reveals a cold-weather story often overlooked.

Where Forests Meet Fossils

The most direct evidence for these polar dinosaurs comes from fossil-rich zones like Dinosaur Cove and Inverloch. However, nearby formations such as the Wonthaggi and Strzelecki Groups, which stretch through South Gippsland, include the same sedimentary layers.

It’s likely that during the Early Cretaceous, continuous forest stretched across what is now Tarra-Bulga, Yarram, and the coast toward Port Albert. River deltas, lakes, and swamps would have provided water and vegetation year-round. With each fossil find from surrounding regions, the case strengthens that Gippsland shared in this prehistoric drama.

Kids of the Cretaceous: Engaging Young Minds

Children visiting Tarra-Bulga today walk under the descendants of those ancient forests. Imagine if they also knew that the very ground beneath them once echoed with dinosaur footsteps.

In schools across Gippsland, there’s opportunity to bring this story to life, not just through museum visits, but by standing in place and asking: What lived here before us? Fossil hunts, dino-trail walks, and illustrated storybooks could all bring these ancient residents into the hearts of local kids.

A Roar from the Past

(artists impression)

The dinosaurs of ancient Gippsland weren’t the colossal icons of pop culture. They were smart, social, and cold-adapted, living under aurora-lit skies in a forested world of shadow and snow.

They are part of this place’s story. Not just as bones buried far away, but as creatures who once called this land home, long before the first humans, and millions of years before the settlers of Port Albert or the loggers of the Strzeleckis.

The next time you walk through the mists of Tarra-Bulga or along the coast near Yarram, remember: this was dinosaur country. And their story is still being uncovered.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection