Supply Pipeline for the Gippsland Goldfields

In the mid-19th century, as gold fever swept through Victoria, Port Albert emerged as a vital hub, connecting the remote and rugged Gippsland goldfields with the bustling world beyond. It was the lifeline for an entire region’s dreams and economic prosperity.

As miners flooded into Gippsland, drawn by the allure of gold in areas like Walhalla, Omeo, Gaffney’s Creek, Dargo, and Foster, Port Albert became their gateway. It was here that the ambitious and the hopeful arrived, some by sea, seeking fortunes in the gold-strewn earth. But Port Albert offered more than just a beginning; it provided the essential links that sustained life and work in the goldfields.

As miners flooded into Gippsland, drawn by the allure of gold in areas like Walhalla, Omeo, Gaffney’s Creek, Dargo, and Foster, Port Albert became their gateway. It was here that the ambitious and the hopeful arrived, some by sea, seeking fortunes in the gold-strewn earth. But Port Albert offered more than just a beginning; it provided the essential links that sustained life and work in the goldfields.

Ships arriving in Port Albert were laden with necessities for the goldfields—tools to dig, equipment to sift, clothing to wear, and food to eat. Without these supplies, life in the remote and often harsh conditions of the goldfields would have been untenable. But Port Albert’s role was twofold; it was also the point from which the fruits of labor—gold—were sent to Melbourne and beyond. This bustling port, with its ships coming and going, was the heartbeat of the Gippsland gold rush, facilitating the flow of goods and gold that fueled the prosperity of the era.

The gold towns serviced by Port Albert never grew into the large cities that other Victorian goldfields spawned, but their stories are no less significant. The gold brought by Port Albert helped to establish solid communities like Bairnsdale and Sale, which thrived on the economic activities the gold rush engendered. Roads and railways, funded by gold, eventually connected these towns more directly to Melbourne, reducing their reliance on the port but never diminishing Port Albert’s critical role in their early development.

Gold stored at the Bank

During the peak of the gold rush, vast amounts of gold, valued today at approximately $7.7 billion, passed through Port Albert. This immense wealth needed safekeeping before it could be transported to Melbourne, presenting a significant challenge. Miners were obligated to store their more precious finds at Customs House, where a duty was levied on gold for export. However, the reputation of Customs House was tarnished by allegations of unfair practices and dishonesty. It was known to charge duty based on the weight of the ore, rather than the actual gold content, a practice that could significantly diminish a miner’s hard-earned findings. Moreover, a scandal involving a local Customs agent arrested for embezzling more than double his annual salary confirmed suspicions of corruption within the institution.

During the peak of the gold rush, vast amounts of gold, valued today at approximately $7.7 billion, passed through Port Albert. This immense wealth needed safekeeping before it could be transported to Melbourne, presenting a significant challenge. Miners were obligated to store their more precious finds at Customs House, where a duty was levied on gold for export. However, the reputation of Customs House was tarnished by allegations of unfair practices and dishonesty. It was known to charge duty based on the weight of the ore, rather than the actual gold content, a practice that could significantly diminish a miner’s hard-earned findings. Moreover, a scandal involving a local Customs agent arrested for embezzling more than double his annual salary confirmed suspicions of corruption within the institution.

Fears among the miners ran deeper than financial losses; they worried that depositing gold with Customs House would leak information about the extent of their finds, potentially triggering a gold rush that could overcrowd their sites and compromise their claims. In search of discretion and safety, they turned to the Bank of Victoria, where their gold could be stored without fear of government prying or public revelation.

The bank, now the very museum in which you stand, became the silent custodian of the miners’ wealth. It steadfastly refused to divulge any details about the gold in its vault, neither the amounts stored nor the identities of the depositors. This commitment to confidentiality made it possible to clandestinely export the gold. In elaborate schemes, gold was hidden in suitcases and entrusted to ship captains for transport to Melbourne, far from the watchful eyes of Customs officials.

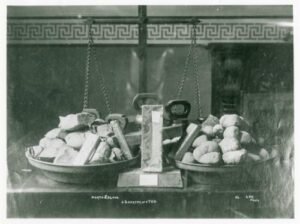

This cloak-and-dagger operation came to a head with the infamous Keera incident. Customs agents, suspicious of a particularly large and heavy “toiletries bag” being handed over to the Keera’s captain – decided to act. Their raid on the ship uncovered 20kg (approximately 1000 oz worth $3.3 million at today’s value) of gold, including sizable nuggets, hidden within the suitcase. This event, detailed in the Gippsland Times on 25 September 1861, underscored the tense relationship between the miners, the bank, and Customs. It was widely known, though never officially acknowledged, that the bank routinely held up to 5000 oz of gold in its vault (worth approx $16.6 million today), a testament to its role as a trusted haven for the miners’ treasure.

This saga of the Bank of Victoria, the Customs House, and the miners who navigated the turbulent waters of gold rush-era regulations and ethics reveals the lengths to which individuals went to protect their wealth and maintain their privacy. It’s a story that brings to life the challenges and ingenuity of those living through one of the most exhilarating periods in Australian history.

Chinese Gold Miners and Port Albert

The gold rush era saw a significant influx of Chinese miners and entrepreneurs, impacting Gippsland’s economic and cultural landscape. Port Albert, a key entry point, played a vital role in this story, offering a gateway to opportunity for thousands from afar.

The gold rush era saw a significant influx of Chinese miners and entrepreneurs, impacting Gippsland’s economic and cultural landscape. Port Albert, a key entry point, played a vital role in this story, offering a gateway to opportunity for thousands from afar.

Port Albert was one of the main entry points for Chinese because the Victorian Government imposed a poll tax of 10 pound on any Chinese arriving into Melbourne. This was a significant amount representing close to $10,000 today in addition to the debt of their fare to the country. As a result many ships chose to land in Port Albert instead.

Some of the earlier Chinese arriving in Port Albert saw an opportunity to develop business to support the goldfields and a large fish curing works was developed here. Recognizing the miners’ need for sustenance, these businesses flourished, providing a critical link in the supply chain supporting the goldfields. This venture was not just about business; it was about creating a self-sustaining ecosystem that allowed for the growth and prosperity of the community, particularly as much of the fish used in the business was purchased from local fishermen.

Most Chinese came to Victoria under the credit ticket system where sponsors paid for their passage to Australia, and in return they would work off their debt through various forms of labor. Some came and paid off their debt at the fish curing works before travelling to the goldfields to mine for themselves. Others however were sponsored by miners and were lured directly to the goldfields under the promise of future fortune. While some were able to venture directly into gold mining and obtained a small percentage of what they found, many were tasked with the essential but less lucrative work of developing infrastructure like dams, water races, and mining equipment, or even farming to support the mining population. These people didn’t earn anything other than their keep until their debt was paid off and many never achieved that before gold became scarce.

Port Albert’s significance during the gold rush, therefore, extends beyond its role as a mere point of entry. It represents a beacon of hope and opportunity, a place where the dreams of thousands were launched, albeit with challenges and obstacles along the way. The legacy of the Chinese in Gippsland, from their entrepreneurial ventures to their contributions to mining infrastructure, remains a pivotal part of the region’s rich tapestry of history, reflecting a story of perseverance, innovation, and significant impact.