On the banks of the Mitchell River or by the edge of Lake Wellington, there are still trees that carry the long vertical scars of bark removed for canoe-making. Yet the canoes themselves — once so common on these waters — are largely gone. Their absence speaks volumes.

With the arrival of British colonisation in the early 19th century, Aboriginal life in Gippsland and across Australia was profoundly disrupted. Canoes, as tools and symbols of mobility, were among the many cultural practices impacted. In this fourth article of our series, we explore how colonisation affected Aboriginal watercraft traditions — from forced displacement and mission life to environmental destruction and loss of intergenerational knowledge. Yet, despite this, canoe culture has not disappeared. Traces remain, and in some places, revivals are underway.

Before Contact: A Maritime Lifeway

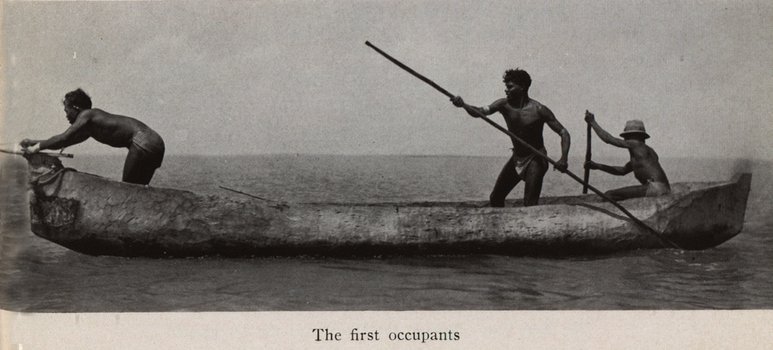

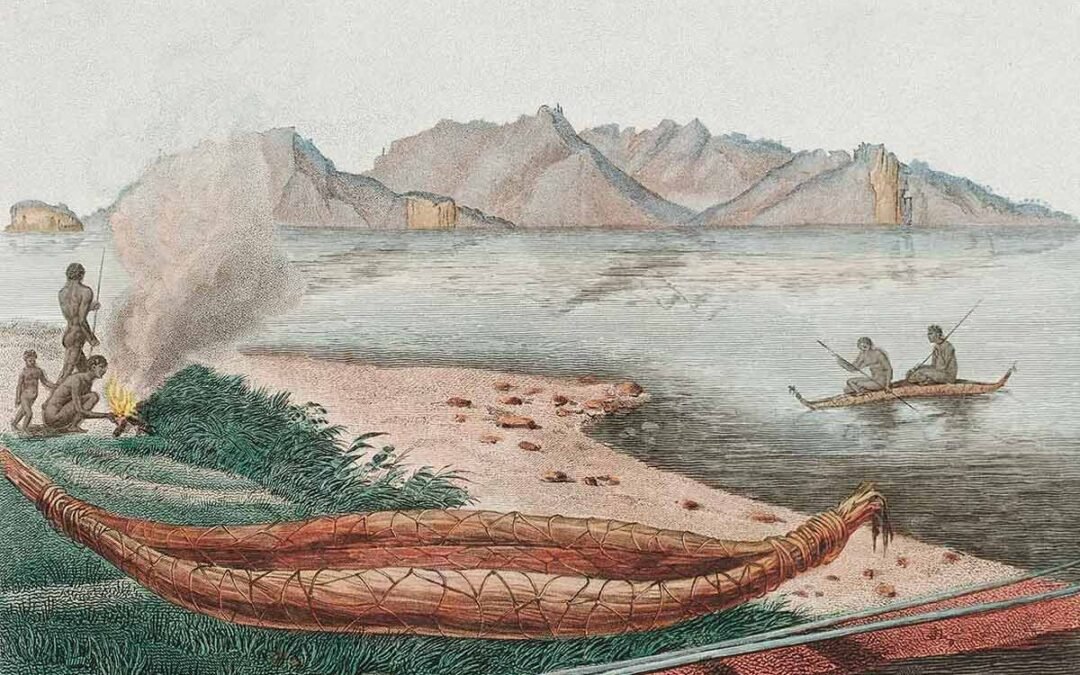

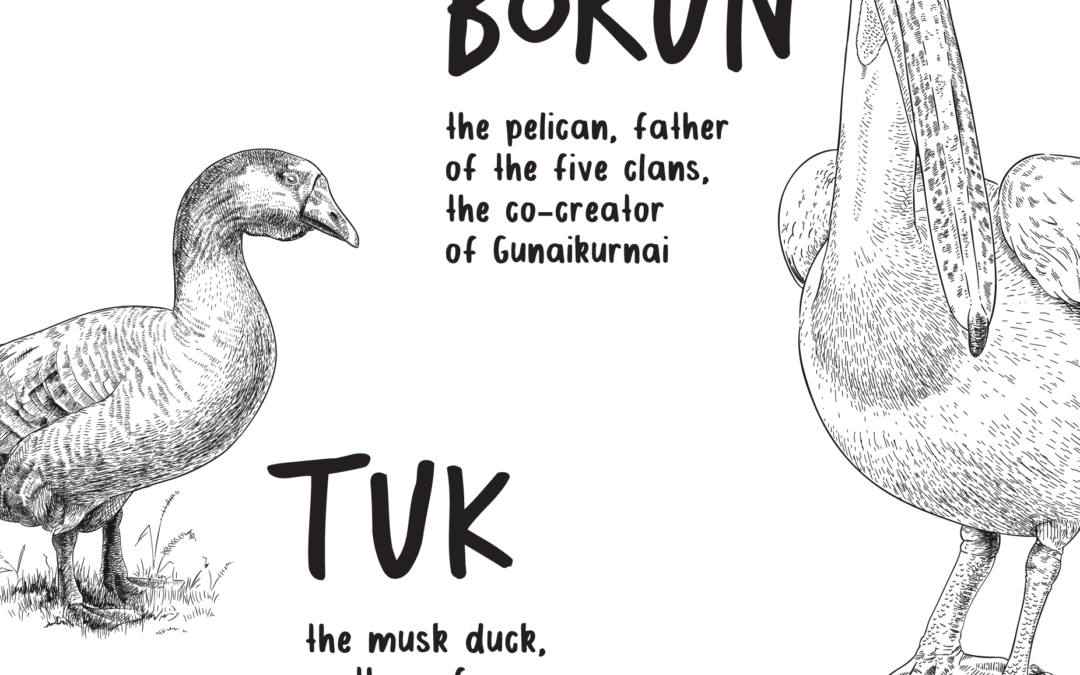

Prior to European arrival, Aboriginal peoples across Australia used a wide range of watercraft — bark canoes in the south and east, dugouts in the north, reed rafts in arid zones, and outriggers in the Torres Strait. In Gippsland, the GunaiKurnai used bark canoes to move between lakes, fish in rivers, and transport families during seasonal movement.

This maritime culture was embedded in every aspect of life: economy, travel, ceremony, and story. Knowledge of canoe construction and use was passed from generation to generation, often linked with lore and language.

The Disruption Begins

The early years of colonisation in Gippsland were marked by violence, land seizure, and forced relocation. For the GunaiKurnai, the arrival of settlers in the 1840s and ’50s led to dispossession of Country, disruption of mobility, and restrictions on access to traditional waterways.

The early years of colonisation in Gippsland were marked by violence, land seizure, and forced relocation. For the GunaiKurnai, the arrival of settlers in the 1840s and ’50s led to dispossession of Country, disruption of mobility, and restrictions on access to traditional waterways.

Three major forces eroded canoe culture:

- Environmental destruction

Logging operations removed many of the old-growth trees needed for canoe bark. Wetlands were drained for grazing, and rivers were diverted or polluted by mining and farming activity. - Displacement and missions

People were moved off Country and placed on missions like Lake Tyers or Ramahyuck. Access to traditional canoe sites was denied, and cultural practices were often actively discouraged or forbidden. - Tool shift and cultural suppression

With the introduction of metal tools, new fishing gear, and European boats, traditional canoes were increasingly replaced — not always by choice. Aboriginal people were pressured to abandon “native” technologies in favour of settler norms.

By the late 19th century, canoe-making in many parts of Victoria had ceased. Only remnants survived — in stories, in trees, and in rare colonial records.

Silencing the River

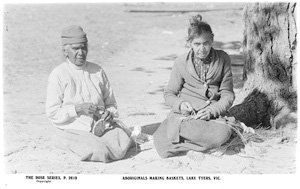

Mission policies, particularly from the 1860s onwards, focused on assimilation. At Lake Tyers, GunaiKurnai families were relocated and made to follow strict daily routines. The use of language and traditional crafts — including canoe construction — was often restricted.

Mission policies, particularly from the 1860s onwards, focused on assimilation. At Lake Tyers, GunaiKurnai families were relocated and made to follow strict daily routines. The use of language and traditional crafts — including canoe construction — was often restricted.

Yet even under these conditions, knowledge was sometimes passed quietly. Children were taught to fish. Scarred trees were remembered. Women continued to weave baskets and set traps, and some Elders continued to speak of the old canoe routes.

Survival in Fragments

While few physical canoes remain from the 20th century, cultural records have helped preserve fragments of memory:

- D.E. Edwards (1972) recorded interviews with Elders from Victoria and NSW, who described how canoes were built and used.

- Scarred trees in Gippsland, especially along the Mitchell, Tambo, and Snowy Rivers, remain visible and protected under heritage laws.

- Early photographs, such as those by Nicholas Caire (c.1886), show bark canoes still in use in eastern Victoria.

These fragments became the foundation for cultural revival work in the 21st century.

Cultural Revival

In 2011, the making of Boorun’s Canoe by Elder Albert Mullett and artist Steaphan Paton marked a major turning point in Gippsland’s cultural history. Using traditional techniques and materials, the canoe was launched on Lake Tyers in front of community and Elders.

In 2011, the making of Boorun’s Canoe by Elder Albert Mullett and artist Steaphan Paton marked a major turning point in Gippsland’s cultural history. Using traditional techniques and materials, the canoe was launched on Lake Tyers in front of community and Elders.

It was the first traditional bark canoe made in the region in over a century.

The project was not just about a canoe — it was about restoring connection. Connection to Country, to culture, and to identity.

“We were taken off the land and away from our waters. But we haven’t forgotten who we are. This canoe helps bring that back.”

— Albert Mullett, 2011

Today, organisations like GLaWAC support this work through ranger programs, cultural education, and heritage protection.

The Role of Museums

Museums have long held Aboriginal objects, often disconnected from their communities. But that is changing. Institutions like Museums Victoria have partnered with GunaiKurnai representatives to co-curate exhibitions, return stories to Country, and use items like Boorun’s Canoe to educate.

At Port Albert Maritime Museum, we recognise the importance of telling not just the technical story of canoes, but the social, historical, and political context of their disruption — and return.

What the Trees Still Say

Scarred canoe trees are not silent. Each one marks a place where knowledge was acted upon, where a community shaped the land to meet its needs. These trees — many near Port Albert and across Gippsland — stand as quiet witnesses to change and continuity.

They remind us that Aboriginal maritime culture was never lost — only interrupted.

Next in the Series: Reviving the Craft: How Canoe-Making Returned to GunaiKurnai Country

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection