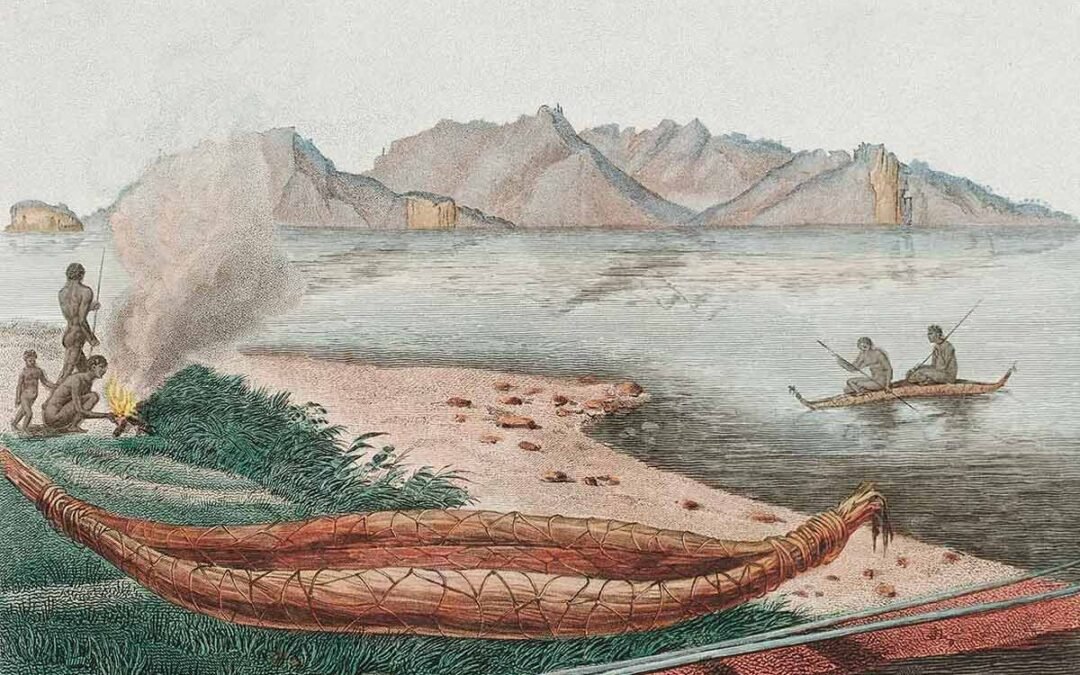

In the forests of Gippsland, a scarred tree stands near the Tarra River. Its bark was removed long ago, but the tree still grows. The scar tells a story — of a canoe made by hand, guided by knowledge passed from one generation to the next. These canoes once carried people along the waters of Port Albert, across Lake Wellington, and along the many rivers that thread through GunaiKurnai Country.

In the forests of Gippsland, a scarred tree stands near the Tarra River. Its bark was removed long ago, but the tree still grows. The scar tells a story — of a canoe made by hand, guided by knowledge passed from one generation to the next. These canoes once carried people along the waters of Port Albert, across Lake Wellington, and along the many rivers that thread through GunaiKurnai Country.

This article looks closely at how bark canoes were built in south-east Australia. Drawing on the work of maritime historian David Payne (2021), and ethnographer D.E. Edwards (1972), we explore the practical skills and cultural knowledge that shaped these vessels — from tree selection to the final launch.

The Bark Canoe: Simple but Sophisticated

Bark canoes were common across much of southern and eastern Australia. They were lightweight, fast, and perfectly suited to calm inland waterways and estuaries. For the GunaiKurnai people of Gippsland, they were essential for fishing, transport, and cultural ceremony.

Despite their simple appearance, bark canoes required careful planning and teamwork. Their design reflected the local environment — the type of trees available, the water conditions, and the purpose of the journey. In Gippsland, red gum and stringybark trees were most commonly used. The canoes had to be light enough to carry, but strong enough to hold an adult and their tools or catch.

Despite their simple appearance, bark canoes required careful planning and teamwork. Their design reflected the local environment — the type of trees available, the water conditions, and the purpose of the journey. In Gippsland, red gum and stringybark trees were most commonly used. The canoes had to be light enough to carry, but strong enough to hold an adult and their tools or catch.

Step by Step: Building a Bark Canoe

- Choosing the Right Tree

The first step was to find a suitable tree. It had to be tall, with straight, thick bark, and located near the water. Red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and stringybark (Eucalyptus obliqua) were often preferred. The time of year mattered — bark came away cleanly in the warmer months when sap was flowing.

“Aboriginal canoe-builders selected trees carefully, often returning to known groves over many years.”

— David Payne, 2021

This was a cultural decision as much as a technical one. Elders and skilled men made the final choice, based on experience and respect for Country.

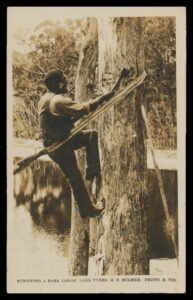

- Cutting and Removing the Bark

Lake Tyers (Gippsland) real photo card by HD Bulmer (Bairnsdale) of Aborigine with tomahawk climbing tree inscribed ‘Stripping A Bark Canoe

The bark was cut in an oval or rectangular shape, usually about three to four metres long and one metre wide. Stone axes, shell tools, or later iron implements were used. Once cut, wooden wedges or levers helped peel the bark from the trunk without splitting it.

The tree was not destroyed. With time, it would heal and continue to grow. These canoe trees, as they are now called, remain as important cultural markers across Victoria, including along the waterways near Port Albert.

- Shaping the Canoe

Once removed, the bark sheet was laid over a small fire or hot coals. Heat made the bark pliable, allowing it to be bent into a shallow U-shape. Wooden props or sticks were sometimes placed underneath to hold the curve.

The ends were drawn up and tied together, usually with natural fibres — such as bark strips, rushes, or vine. In Gippsland, the bow and stern were kept slightly open, giving the canoe a wide, stable base.

D.E. Edwards, writing in 1972, described this as “a flexible form of watercraft, easily shaped and adapted to suit the needs of the local river or lake.”

- Sealing and Strengthening

To make the canoe watertight, the joints were sealed with clay, resin, or chewed-up grass. In some areas, beeswax or animal fat was used. Extra strengthening ribs could be added inside, but many Gippsland canoes relied on the natural strength of the bark.

Paddles were simple but effective — usually made from a flattened stick, with one end rounded or slightly shaped.

Built by Hand, Informed by Culture

Bark canoes were usually made by men, though women played important roles in gathering materials and in teaching younger generations. Building a canoe was not just a technical task — it was cultural work. The act of removing bark, shaping it with fire, and launching it into water was guided by knowledge systems that included respect for the tree, the river, and the ancestors.

In some communities, canoes were built for specific events — a seasonal fishing trip, a ceremonial journey, or a marriage exchange. Each canoe carried the imprint of the land it came from.

In the words of Elder Albert Mullett (2011), “The canoe is not just a canoe. It’s who we are.”

Practical Design

Gippsland bark canoes were designed for inland lakes and rivers, not open ocean. They were:

- Lightweight: so they could be carried between waterways

- Wide and stable: for fishing and carrying tools or children

- Easily repaired: using natural materials found along the banks

D.E. Edwards recorded that canoes in south-east Australia could last for weeks or months, depending on usage and storage. Some were left by the river for regular use. Others were made for a single trip.

What the Canoe Trees Still Tell Us

Though the canoes themselves no longer survive, the trees do. All across Gippsland, including near Port Albert, scarred trees still mark the places where canoes were made. Their scars — vertical, oval-shaped wounds — are now protected as Aboriginal cultural heritage.

They remind us that these were not just boats, but part of a much larger system of knowledge, land care, and community.

Continuing the Practice

In 2011, Albert Mullett and his grandson Steaphan Paton made the first traditional bark canoe in Gippsland in more than a century. Using red gum bark, fire, and traditional bindings, they shaped a canoe by hand and launched it on Lake Tyers.

In 2011, Albert Mullett and his grandson Steaphan Paton made the first traditional bark canoe in Gippsland in more than a century. Using red gum bark, fire, and traditional bindings, they shaped a canoe by hand and launched it on Lake Tyers.

The canoe, called Boorun’s Canoe, is now held by Museums Victoria and featured in the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre. It is a living reminder of a skill that was nearly lost — and a powerful act of cultural renewal.

In Port Albert and Beyond

Here in Port Albert, at the edge of the Tarra River, the story of bark canoe-making is close to home. This region was once a hub for water travel, with GunaiKurnai people moving between freshwater and saltwater environments by canoe.

As a maritime museum in the heart of Gippsland, we are committed to sharing these histories not only as records of the past, but as part of the ongoing story of cultural strength and continuity.

Next in the Series: River Lives – How Aboriginal Women and Men Used Canoes Differently

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection