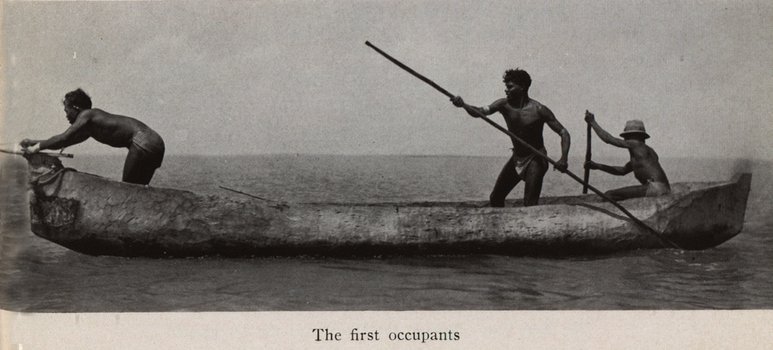

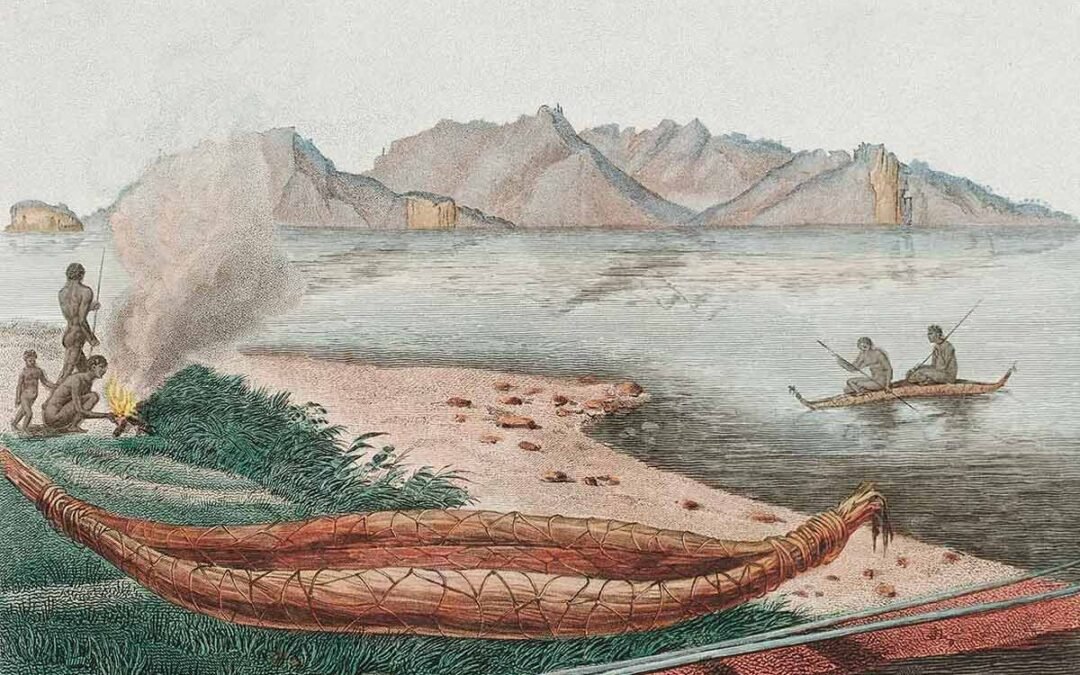

On the still waters of the Gippsland Lakes, a woman once paddled a small bark canoe, a child seated in front of her, a small fire lit in the rear for cooking shellfish. Her husband, perhaps further out in deeper water, stood poised in a larger canoe, spear ready. Both moved with confidence and grace, each performing roles learned through generations of lived experience. These were not just family outings — they were part of an organised and adaptive water-based economy, shaped by Country and culture.

On the still waters of the Gippsland Lakes, a woman once paddled a small bark canoe, a child seated in front of her, a small fire lit in the rear for cooking shellfish. Her husband, perhaps further out in deeper water, stood poised in a larger canoe, spear ready. Both moved with confidence and grace, each performing roles learned through generations of lived experience. These were not just family outings — they were part of an organised and adaptive water-based economy, shaped by Country and culture.

In this third article of our series, we explore how Aboriginal men and women used canoes in different, complementary ways. Drawing from detailed observations by ethnographers like D.E. Edwards (1972), and from cultural knowledge maintained by GunaiKurnai people, we highlight how watercraft were embedded in everyday life, and how those practices differed according to gender, age, and region.

Canoes in Daily Life

In communities across south-eastern Australia — including Gippsland — canoes were central to subsistence. Men and women used them not just for movement but to access and gather key resources.

In communities across south-eastern Australia — including Gippsland — canoes were central to subsistence. Men and women used them not just for movement but to access and gather key resources.

Men generally used canoes for:

- Spear fishing in deeper waters

- Hunting waterbirds with throwing sticks

- Longer-distance travel between family groups

- Transporting materials and trade goods

Women typically used canoes for:

- Harvesting shellfish (mussels, pipis) in shallow areas

- Collecting water plants, such as cumbungi (bulrush) and nardoo

- Caring for young children during travel

- Setting eel traps and baskets

One of the more remarkable practices involved women balancing small cooking fires at the rear of their canoes. These fires were used to prepare food while out gathering. D.E. Edwards documented this in several south-east Australian communities, noting the canoe’s broad design allowed for safe fire use without tipping — a testament to Indigenous knowledge of stability and function.

Gendered Knowledge and Craft

Canoe use was part of a broader system of gendered roles. While men typically built the canoes, women were closely involved in their maintenance and use. Knowledge was passed down within family lines — grandfathers to grandsons, grandmothers to granddaughters.

Each group’s techniques were shaped by their local waters:

- On Lake Tyers and the Mitchell River, women worked in wide, stable canoes well suited for still water.

- In faster-flowing rivers like the Tarra, men used narrower, more manoeuvrable craft for precision spear fishing.

This division of labour was not rigid — roles could overlap, and everyone learned to handle a canoe from a young age. Children joined their parents early and quickly developed balance and coordination, often helping paddle or manage catch.

Canoes and Ceremony

Beyond everyday use, canoes held cultural significance.

In some communities, bark canoes featured in initiation rites — young men would paddle to a ceremonial ground, or prove their skill on the water. Funerary practices also sometimes involved canoes: either to transport the deceased or, symbolically, as vessels to carry a spirit home.

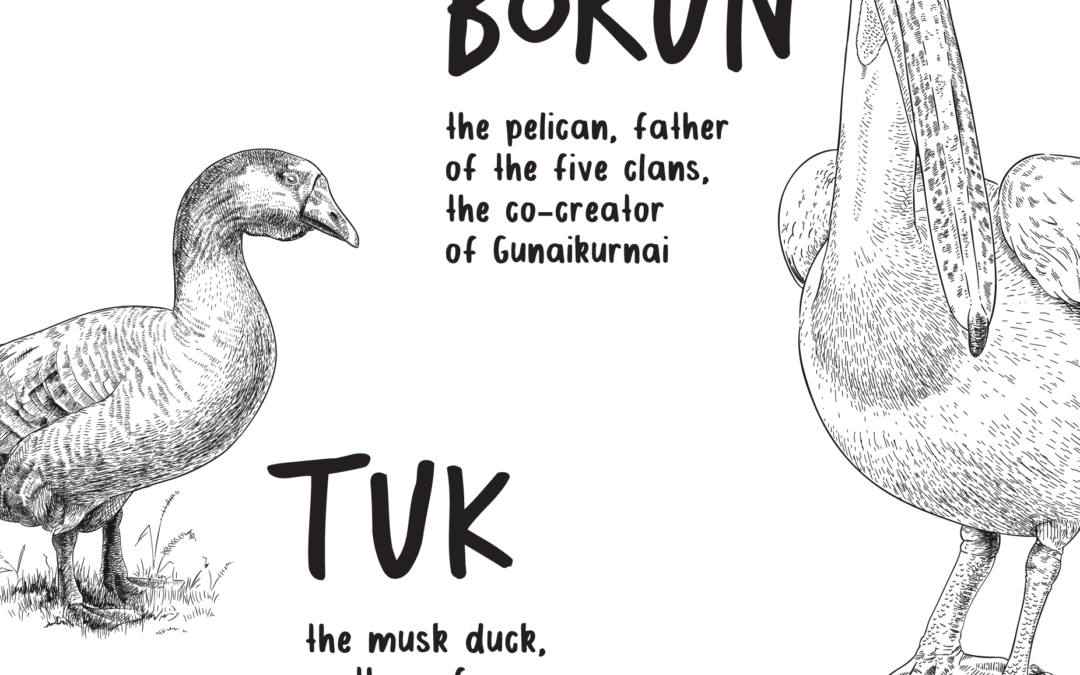

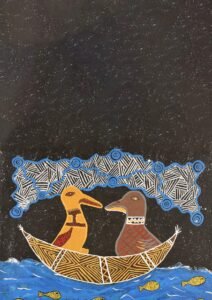

In oral histories and songlines, canoes appear frequently as markers of journey, movement, and transformation. Among the GunaiKurnai, the creation story of Borun the Pelican begins with a canoe — one that carried him from the high country to the sea. At Port Albert, where the Tarra River meets the ocean, Borun first heard the footsteps of Tuk the Musk Duck. That canoe was not just a vehicle — it was a part of identity, kinship, and law.

In oral histories and songlines, canoes appear frequently as markers of journey, movement, and transformation. Among the GunaiKurnai, the creation story of Borun the Pelican begins with a canoe — one that carried him from the high country to the sea. At Port Albert, where the Tarra River meets the ocean, Borun first heard the footsteps of Tuk the Musk Duck. That canoe was not just a vehicle — it was a part of identity, kinship, and law.

Seasonal Movement and Canoe Clans

GunaiKurnai people moved seasonally across their Country. Canoes enabled this movement — allowing families to follow eel migrations, reach coastal fisheries, or attend gatherings. Clans such as the Brataualung and Tatungalung, who lived near water year-round, had particularly strong canoe traditions.

David Payne (2021) notes that canoe use was deeply embedded in the landscape: “Waterways were living corridors, and the canoes were adapted to each bend, bank, and beach.”

Women’s Economic Role on Water

Anthropological records and early settler diaries (though limited in scope) confirm the important economic role of women in canoe-based resource collection.

- At Lake Tyers Mission, women were known to maintain fishing spots and pass down net-making skills.

- In eastern Gippsland, eel farming and basket trapping were often led by women — requiring knowledge of seasonal water flow, lunar cycles, and plant-based construction.

This contradicts stereotypes that placed men as the primary providers. In reality, the canoe was a shared tool in a shared economy.

Children and Learning

From a young age, children were involved in canoe life. Small bark sheets were often used as toy canoes, and games on the river became training in balance and control. By adolescence, both boys and girls could paddle independently and participate in fishing or gathering.

Elders taught through observation, correction, and storytelling — and these lessons were layered with cultural knowledge. To know how to handle a canoe was to know how to read the river, how to behave respectfully, and how to care for Country.

Then and Now

With colonisation, many of these practices were disrupted. Canoes were often replaced by European-style boats, and many women were confined to missions or displaced from their waters. However, knowledge persisted in fragments — through oral tradition, memory, and place.

Today, organisations like GLaWAC (Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation) support cultural renewal projects, including those that bring young people back onto water. Events like the revival of Boorun’s Canoe in 2011 honour both male and female roles in canoe culture. Elders, rangers, and artists work together to ensure that the next generation not only paddles again, but understands the stories carried in each stroke.

In the Museum Context

At the Port Albert Maritime Museum, we view canoes not just as objects of engineering, but as reflections of social life. By understanding how different members of the community used them — and the knowledge systems behind them — we deepen our understanding of this region’s maritime heritage.

The rivers, lakes and inlets of Gippsland remember these movements. So too do the scarred trees, the fishing grounds, and the stories passed on by Elders.

Next in the Series: From River to Ruin — How Colonisation Disrupted Watercraft Traditions

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection