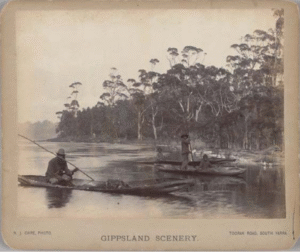

On a still morning in Gippsland, where the Tarra River slips through swamplands toward the sea, mist clings to the reeds and eucalypts. Long before ships docked at Port Albert, this waterway was part of a vast Indigenous network – a living highway. Along it, a figure would glide silently in a bark canoe, tracking ancestral stories etched in the currents and trees.

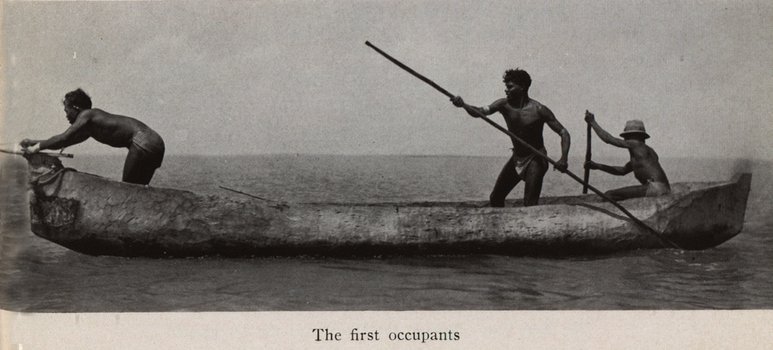

Australia’s First Nations peoples were not just custodians of land – they were skilled mariners, engineers, navigators. From the vast river systems of the Murray-Darling Basin to the ocean swells of the Torres Strait, Aboriginal communities designed and built sophisticated watercraft perfectly adapted to their Country. These vessels carried families, food, trade goods, ceremony – and stories. They continue to hold cultural and environmental wisdom spanning tens of thousands of years.

This introductory article in our series explores the extraordinary diversity of Indigenous Australian watercraft, focusing on how design reflected environment, function, and cultural knowledge. Later articles will turn our lens more closely to the canoes of Gippsland and the traditions of the GunaiKurnai peoples – for whom Port Albert holds particular ancestral significance.

This introductory article in our series explores the extraordinary diversity of Indigenous Australian watercraft, focusing on how design reflected environment, function, and cultural knowledge. Later articles will turn our lens more closely to the canoes of Gippsland and the traditions of the GunaiKurnai peoples – for whom Port Albert holds particular ancestral significance.

A Continent of Canoes

Indigenous Australians used watercraft across an estimated 70 percent of the continent, from rainforest rivers to desert wetlands. While local materials and environments shaped their forms, all vessels shared one feature: they were designed with deep ecological intelligence.

As David Payne, maritime curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum, observes:

“These are craft whose design comes from a thorough understanding of the regional geography and botany… All are appropriate to their role.”

“These are craft whose design comes from a thorough understanding of the regional geography and botany… All are appropriate to their role.”

— David Payne, 2021

Four major categories of Aboriginal watercraft have been identified:

- Bark Canoes

- Found widely across southern and eastern Australia, including Victoria.

- Constructed by removing large sheets of bark from trees such as stringybark or red gum.

- Flexible and fast; ideal for rivers, estuaries, and lakes.

- Dugout Canoes

- Carved from whole logs, typically in the tropics.

- Heavier, more robust, better suited to coastal and deep-water travel.

- Rafts and Bundled Canoes

- Made from mangrove poles, reeds, or melaleuca bark.

- Used in desert floodplains and parts of Queensland.

- Outrigger and Double-Hulled Canoes

- Built in the Torres Strait Islands and northern Cape York.

- Capable of extended sea voyages and long-distance trade.

Each form reflected not only its maker’s environment but also their social and ceremonial life. No two communities built their watercraft identically — even neighbouring groups might differ in bark choice, construction techniques, or usage protocols.

Purpose and Precision

These vessels were far more than tools. They enabled a sophisticated interaction with Country and were embedded in the rhythms of daily life.

- Fishing and Gathering: Women in many cultures used small canoes to collect shellfish, set eel traps, or harvest aquatic plants. Men speared fish from larger vessels or hunted waterfowl with extraordinary dexterity.

- Trade and Travel: Canoes linked distant communities. Along river systems like the Murrumbidgee or Snowy, people traded ochre, tools, and songs. In Arnhem Land, dugouts crossed to offshore islands and met with Macassan sailors from Indonesia.

- Ceremony and Storytelling: Canoes often featured in initiation rites and mortuary practices. Some were used to carry ceremonial dancers. Others were left as offerings.

In all cases, watercraft were expressions of cultural identity. Their construction required group cooperation, seasonal timing, and adherence to spiritual laws.

Navigators of Sky and Stream

Contrary to outdated assumptions, Aboriginal mariners possessed sophisticated navigational skills. In tidal waters, they read swell patterns and sea breezes. In riverine environments, they memorised eddies, landmarks, and bird movements.

Some travelled by starlight. Others followed sound — the echo of fish splashing, the whisper of reeds — to guide their course. In Torres Strait, celestial navigation systems were as complex as those in Polynesia.

To travel by canoe was not only to reach another place, but to move through a landscape of meaning.

Gippsland’s Waterways: Bark Canoes and the GunaiKurnai

Nowhere is this more evident than in the lake-strewn country of south-eastern Victoria. Here, in the land of the GunaiKurnai, bark canoes were central to mobility, subsistence, and story.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the lake-strewn country of south-eastern Victoria. Here, in the land of the GunaiKurnai, bark canoes were central to mobility, subsistence, and story.

The five clans — Brataualung, Brabralung, Tatungalung, Krauatungalung, and Brayakaulung — built canoes from the large eucalypts lining the rivers and lakes. On the tranquil waters of Lake Wellington and Lake Tyers, people fished, travelled, and conducted ceremonies.

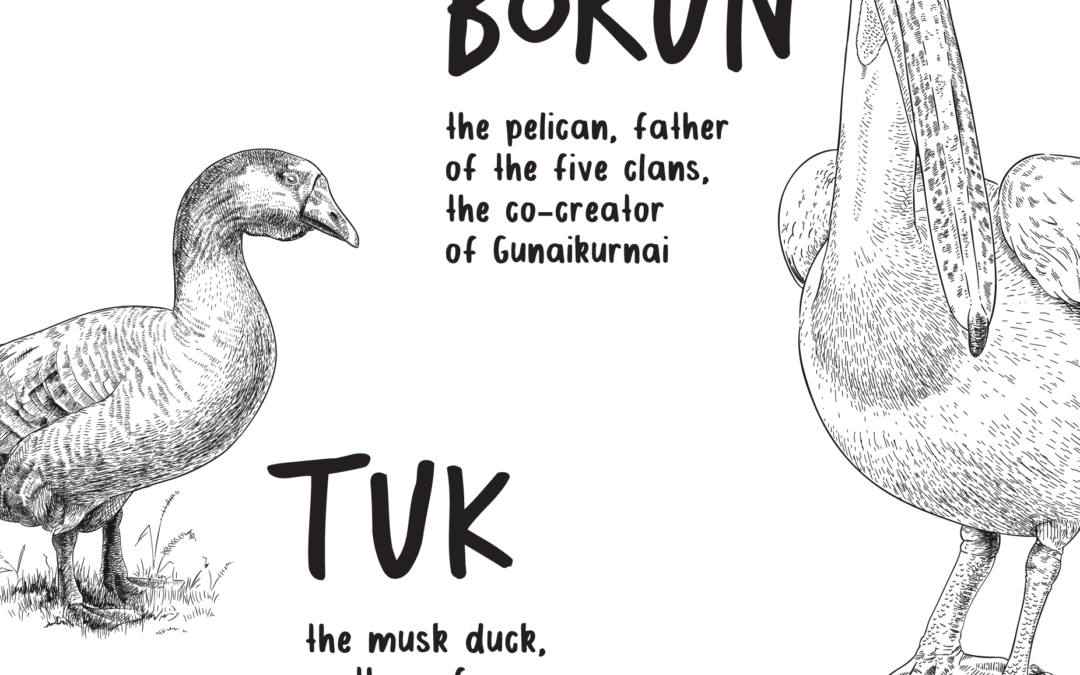

Port Albert, near the mouth of the Tarra River, holds a place of special cultural significance. It is here that the GunaiKurnai creation story begins. Borun the Pelican, the first ancestor, journeyed from the high country carrying a bark canoe. He stopped at Tarra Warackel — the site of present-day Port Albert — where he encountered Tuk the Musk Duck. She became his partner, and together they gave rise to the five clans.

“Borun carried his canoe across Country. It brought him to the place where our people began. That canoe is part of who we are.”

— Albert Mullett, GunaiKurnai Elder

This story is not simply metaphorical. It encodes ecological knowledge, spiritual law, and kinship structure — all through the motif of the canoe.

Scarred Trees and Silent Witnesses

Today, few traditional bark canoes survive. The materials were designed to return to Country after their use — and colonial disruption accelerated their disappearance.

Today, few traditional bark canoes survive. The materials were designed to return to Country after their use — and colonial disruption accelerated their disappearance.

Yet evidence remains. Scarred trees, where bark was cut for canoes, still line rivers across Gippsland. These trees bear the signatures of ancestral craftsmanship. Their presence affirms an enduring maritime culture — one grounded not in ships and sails, but in bark, balance, and belonging.

As Payne notes, Aboriginal watercraft “stood at the centre of life on water, just as fire did on land” (2022). To revive them is to reignite more than technique — it is to kindle memory.

Towards Revival

In 2011, a powerful act of reclamation took place. GunaiKurnai Elder Albert Mullett passed down the knowledge of canoe-making to his grandson Steaphan Paton. Together they built a traditional bark canoe, using only cultural materials and methods.

Launched on the waters of Lake Tyers, the canoe floated gracefully — the first of its kind made in the region in over a hundred years. Documented in photographs by Cam Cope and later displayed at Melbourne Museum’s Bunjilaka Centre, it became a symbol of revival.

The canoe was named Boorun’s Canoe, in honour of the ancestral pelican. It was not a reconstruction — it was a continuation.

Looking Forward

At Port Albert Maritime Museum, we believe these stories — and the skills behind them — are vital to understanding Australia’s maritime heritage. Over the coming months, we’ll explore in detail:

- How bark canoes were constructed in Victoria’s forests.

- Gender roles and cultural protocols surrounding canoe use.

- The colonial disruptions that nearly erased them.

- And the inspiring contemporary efforts to revive them — right here in Gippsland.

As we travel through this series, may we come to see the rivers not just as watercourses, but as archives. And the canoes that once slipped through them — as pages in the oldest navigational story ever told.

Next in the Series: Crafting the Current: How Bark Canoes Were Built in South-East Australia

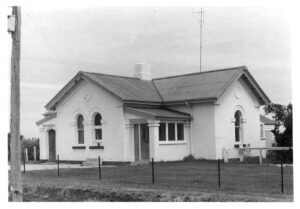

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees.

Today it remains a private residence, carefully restored and adapted for modern use. More recent owners have retained its defining features – high ceilings, arched windows, Baltic pine floors, and solid brickwork – while adding an accommodation wing at the rear. The building sits within a 1,597 square-metre block overlooking the historic Government Wharf, its courtyard shaded by mature trees. The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility.

The Port Albert post office was built in a conservative Italianate style, a restrained interpretation of the architecture popular in Melbourne during the 1860s. Its symmetrical façade, bracketed eaves, and tall arched windows gave the small coastal town a touch of metropolitan civility. Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured.

Port Albert’s prosperity peaked in the 1860s. As railways reached inland towns, trade routes shifted, and larger ships bypassed the shallow inlet. The port declined, but the post office endured. An Enduring Connection

An Enduring Connection